It’s hard to practice what you preach

If there’s anything that twenty years of listening to stories from the margins has taught me, it’s this: we humans need to feel that life doesn’t just happen to us; that we can make things happen. And, we need to feel we aren’t alone. We crave agency — the capacity to originate action — and belonging.

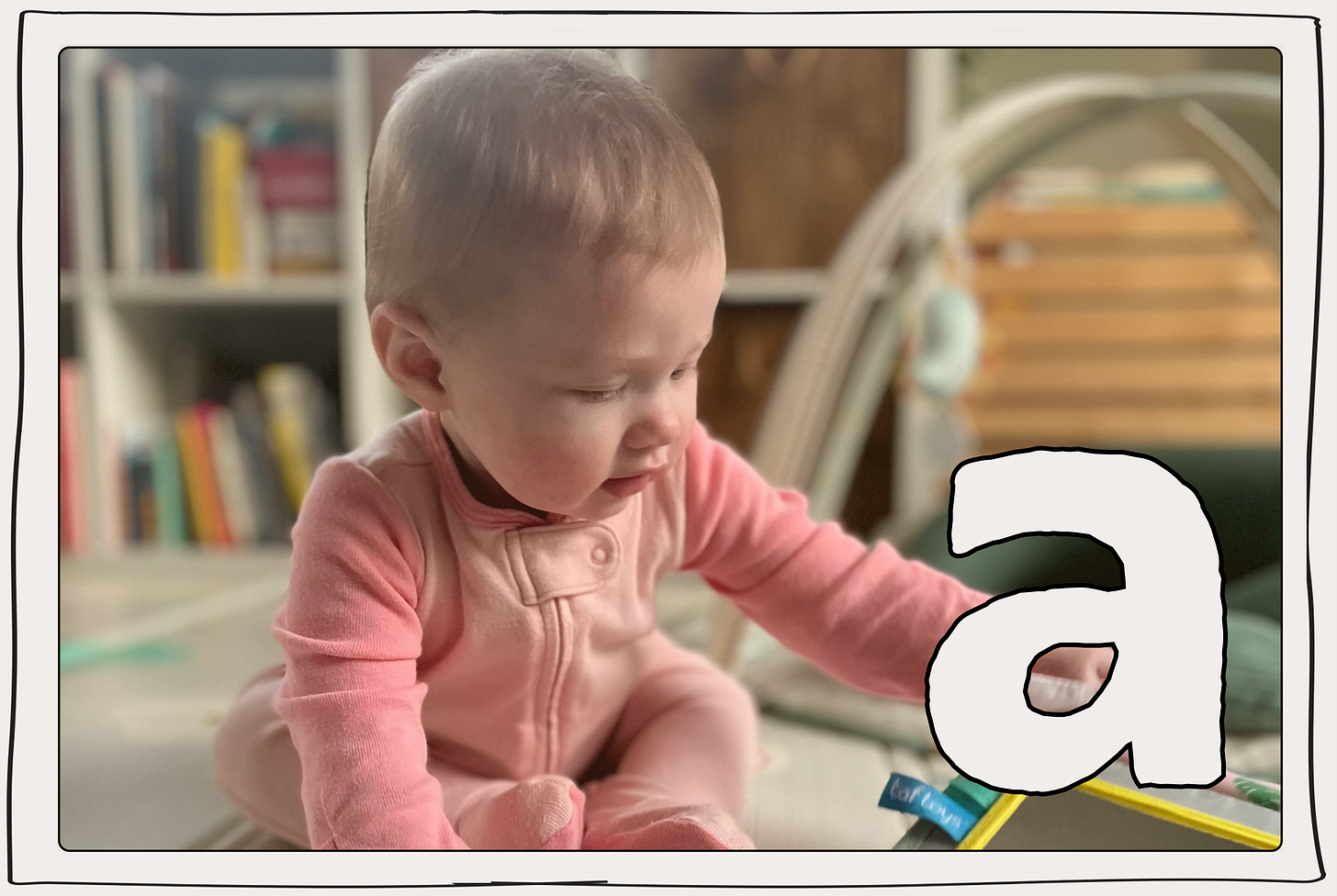

Yet, as a new mama, I’ve struggled to trust that my little one knows what she needs and is capable of exercising agency.

At four months old, just as we were finding our combo-feeding rhythm, she developed a bottle aversion. Saying ‘no’ to the bottle, by contorting her body and forcefully shoving it away, became the only way she could exert control in a context where I held so much power.

Rather than listen to what she was wanting (or not wanting), I pushed my agenda: eat! Out of worry, fear, and love. My need to ensure she was well fed impinged on her need to regulate how much she ate. We got stuck in a negative feedback loop. Legally, we refer to children as our dependents. But, really, she and I are inter-dependent. Her needs, desires, behaviours, and choices are shaped in relation to mine, as are mine to hers.

Agency both animates individual lives and unfolds within relationships.

Exiting the negative feedback loop required resetting our relationship. Rather than try and control her eating, I redirected my agency towards creating the conditions for mutual nourishment. I could put on music, get comfortable, be present, and tune-in to her body language. Within three days, she regained her appetite.

The impulse to exercise control over another human -- especially those we see as vulnerable -- shows up in so many of our social services and systems. And, just as I observed with my little one, the more we use our agency to impede another’s agency, the more we can foment the very behaviours we fear.

Two stories that stick with me

Mark lived in a ground floor apartment alone. He had one plate, one fork, and one knife because he always ate by himself. The one photograph on his wall showed a beaming Mark, alongside his parents, graduating high school.

When we met fifteen years later, the promise of graduation had long been replaced by the mundane realities of a day program for people with developmental disabilities. Mondays were bowling days. Tuesdays were spaghetti for lunch. Wednesdays included a trip to the mall. Mark didn’t like bowling. He was tired of spaghetti, and wanted to make a roast. He imagined hitting the open road to travel. The more Mark was prevented from living the life he wanted, the more frustrated he became. He used what little agency his context afforded him to resist. He stopped talking. He started biting. He used physical force. Staff had to write-up critical incident reports. The more critical incident reports on file, the more constraints he faced. At times, he was even physically restrained. Mark and his staff were locked into a negative feedback loop.

So was Alexa.

By the time Alexa was 21-years-old she had been detained 21 times under the Mental Health Act. Removed from her mother and grandmother’s care as a young child, and placed into a revolving door of foster homes, Alexa found drugs blunted the extreme pain. Maybe she didn’t want to survive: what was there to live for? Over and over again, professionals determined Alexa didn’t have the capacity to make good decisions for herself. Her life was at risk and so they could justify taking away her agency and committing her to a hospital treatment program. Only for Alexa the loss of agency affirmed her negative self-narrative: that bad stuff happened to her; that she didn’t deserve love; that she had no control. What Alexa most wanted -- for somebody to give her a hug, acknowledge her pain, and help her regain a healthy sense of agency -- was most out of reach.

Dehumanizing logics

Fostering agency isn’t an activity or outcome we typically see prioritized by social services. It makes sense. Our welfare system was set-up for different purposes: to keep ‘vulnerable’ people safe, reduce the risk of bad things happening, and enforce a set of normative behaviours like going to school, holding a job, and staying out of trouble. Under the lens of protectionism, we have long accepted constraints on ‘vulnerable’ people’s agency. It’s in their best interest, we say, to make decisions on their behalf because we trust our good intentions more than we trust their capacity for agency. And, of course, it’s complicated. Some people may need assistance with most of the activities of daily living - from feeding to toileting - and have few ways of communicating their needs and desires. The challenge is we lump an incredibly varied set of people under the banner of ‘disability’ ‘mental illness’ and, the catch-all phrase, ‘vulnerable,’ and in the process, treat agency as all or nothing.

Much of the literature on agency starts with the assumption that:

Agency is a defining feature of being human, and

Agency is a cognitive capacity, requiring a certain level of rationality & self-awareness. You either have it, or don’t.

Taken together, we arrive at a profoundly unsettling place: if people do not meet the cognitive threshold, are they somehow not human and with less moral worth?

This is the same logic underlying institutionalization and forced sterilizations of people with disabilities and mental illnesses. And while modern societies have largely come to view these interventions as dehumanizing, the question marks live on. Even without bricks and mortar institutions, plenty of practice within foster homes, group homes, day programs and shelters is predicated on professionals - be it doctors, nutritionists, behavioural analysts, social workers, or other staff -- knowing best. We aren’t so sure we can allow people with addictions or disabilities to exercise agency because we aren’t so sure of their competence.

In his book Speciesism and Moral Status, the philosopher Peter Singer bluntly argues that people with significant cognitive deficits are incapable of moral agency: they cannot understand or abide by social contracts; they cannot contribute to the lives of others; and they cannot conceive of themselves as ‘selves’ over time.

Another way to see agency

What Singer seems to overlook is a life course perspective. Our cognitive capacities are not fixed. They develop and recede over time, and are enabled or hindered by our contexts. My little one has a remarkably good sense of what her body needs and how to act so those bodily needs are fulfilled, but a pretty poor sense of how to operate in an environment full of mortal risks. While she has yet to develop higher-order cognitive skills, and is blissfully unaware of our social contract, she very much contributes to the lives of others. That is also the conclusion of the ethnographer Patrick McKearney, who embeds himself within a L’Arche home for adults with significant developmental disabilities, and learns that “people with cognitive disabilities are surprising, eccentric, and charismatic agents who can powerfully affect the ethical lives of others.”

In their paper, The inseparability of human agency and linked lives, the authors S.D Landes and R.A. Settersten argue that the problem doesn’t lie with people with cognitive deficits, but with how we’ve come to define agency as an individual characteristic. “Agency,” they write, “is intimately dependent upon interpersonal relationships -- a hallmark of the human condition at all times in the life course, even for those who are ‘developmentally normal.’” Independence, they note, is a fallacy.

“No person is completely independent - even, and perhaps especially in the many decades of adulthood as we rely on one another for physical and emotional care, encouragement, and social and material support, and as we simultaneously hold roles of spouse, parent, worker, and other statuses that deepen our interdependence with others.”

Maybe it all sounds a bit conceptual. But, surfacing ideas about independence, agency, and control isn’t simply an academic exercise. Our underlying ideas have big real world implications. In his research, Professor Julian LeGrand convincingly shows, “Assumptions concerning human motivation - the internal desires or preferences that incite action - and agency - the capacity to undertake action - are key to the design and implementation of public policy. Policymakers fashion their policies on the assumption that both those who implement the policies and those who are expected to benefit from them will behave in certain ways, because they have certain kinds of motivation and certain levels of agency.”

So, what would our health & social systems look like if we understood agency to be relational, not simply individual? Well, for starters, the doctor’s appointment my little one and I just had wouldn’t just focus on whether she is meeting her developmental milestones, but on how to set-up our home and engage as a family unit to grow our interdependence and mutual sense of agency.

Now, it’s your turn. What can you imagine?

CONCEPT RECAP

What is agency?

“To be an agent is to influence intentionally one’s functioning and life circumstances.” - Albert Bandura

The capability to act and be “the perpetrator of events” - Anthony Giddens

What’s the rub?

On the one hand, agency is a defining characteristic of being human.

On the other hand, a lot of the literature frames agency as a higher-order capability, one that requires rational and reflective thought. To be an agent is to express desires, formulate strategies, self-assess, and course correct.

If we accept that agency requires a certain level of cognitive ability, then we relegate people who lack this cognitive ability to not being fully human.

Is there an alternative framework?

We can look at agency as a product of our relationships and contexts, not simply as an individual characteristic. We could not exist without others.

Agency and interpersonal dependence co-exist.

As the authors S.D. Landes and R.A. Settersten write, “Any conceptualization of agency demands attention to the ways in which it is created, fostered, diminished, or eliminated in the context of interpersonal relationships.”

Why does agency matter?

Agency is strongly associated with health & wellbeing.

The absence of of agency undermines basic functioning and dampens reasons for living.

Assuming some people lack cognitive capacity for agency rationalizes their dehumanization.

How can you apply this idea?

You can continually ask yourself: For each relationship I am in, what are the ways in which my agency is fostered, diminished or eliminated? And what are the ways in which I foster, diminish, or eliminate the other party’s agency?

Want to read more?

Read the article The inseparability of human agency and Linked Lives

Read Receiving the gift of cognitive disability: Recognizing agency in the limits of the rational subject

Read Toward a psychology of human agency (one of the classics!)