“When our gaze falls onto a thing of beauty, we are no longer at the centre of the world.” - Nancy Perkins Spyke

It’s one of those early mornings when my to-do list runs mind loops to a bullet point soundtrack. Rain slaps the roof. Fog obscures the view. I slide open the door to her room. She is sitting up in her lilac sleep sack waving at her friends slouched on the shelf. There’s Tully, the turtle; Sally Douglas, the sloth; Freddy, the frog; and Kip, the kangaroo. “EH, EH. EH” she squeals, viscerally delighted to be reunited with her fellow animals.

I grin and join in the morning salutations.

The weight of the day is temporarily displaced by the beauty of the moment — by my little one’s expansive expression of camaraderie, by her sense that everything is alive.

Inspired by her generosity, I try to spend the day tuning into all that is alive; to all that cannot be contained by a bullet point on a to-do list. Like effervescent green moss hugging the tree outside my front window. Like the man at a busy coffee shop playing his flute to calm a flustered stranger (me). Like Manitoba Premier Wab Kinew singing a Lakota song of remembrance at a press conference for Ashlee Shingoose, whose remains are finally returning home. Each of these moments lifts me out of myself just long enough to breathe, to marvel, to cry, to feel moved. Beauty momentarily frees me from my day-to-day stupor.

I think this is what the philosopher Peg Zeglin Brand is getting at when she writes,

“Beauty seems in need of rehabilitation today as an impulse that can be as liberating as it has been deemed enslaving.”

Cut loose from the shackles of consumer capitalism, beauty offers us something more magical than perfection — a palpable sense of relief, reengagement with our senses, an open door to renewal and reinvention.

One of the joys of ethnography on the edge — of bearing witness to marginalized lives and contexts — is finding beauty in what others’ have invisibilized and rendered unsightly. As one of the poorest postal codes in Canada, Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside is so many things: blocks of tents and twisted bodies; open flows of goods, services, and care; and intersecting layers of personal, cultural, and political histories.

And yet to many tourists, passersby and “tough on crime” politicians, the Downtown Eastside is little more than urban blight; a public safety scourge. “Stay away” was what my seat mate advised on my first flight to Vancouver. I did not. I could not. One muggy summer evening while shadowing James, a theologian who had long worked in the shelters before finding himself using the shelters, I watched as an older man pushed a bike with a trailer full of tubs of rainbow ice cream. He stopped in the middle of the street as a crowd gathered, gleeful for a goopy, multi-coloured scoop. Someone, somewhere, pulled out a bag of cones. Another group unveiled a cooler full of meat. Let’s call it creatively sourced. Speakers blared. We danced. Here we were on a Thursday night in the midst of an impromptu street party. Living in a city where zoning regulation thwarts public dancing, the sense of movement and full expression of joy, big-heartedness, and solidarity was breathtakingly beautiful — even as the beauty co-existed with so much tragedy and pain.

Like the Downtown Eastside, beauty is many things. The classical definition of beauty is proportionality and symmetry. The integration of parts into a whole. But, beauty constantly surprises us. It cannot be captured by a checklist. It is zesty. It is resonant. It pulls us outside of ourselves to appreciate, to marvel, to play, to emote. For the German playwright and poet Friedrich Schiller, beauty “performs the process of integrating or rendering compatible the natural and the spiritual, or the sensuous and the rational: only in such a state of integration are we — who exist simultaneously on both these levels — free (as quoted in Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy).”

Perhaps because beauty cannot be pinned down, patriarchal and market forces have tried mighty hard to contort beauty into a tool of oppression. We are told we need to look a certain way to be beautiful. We are told we need to buy beautiful things to be worthy. For those of us who look and act different to the norm and who cannot afford to buy beautiful things, beauty is cast aside as superfluous and irrelevant. It is rare to find social policy or social services that explicitly talk about or prioritize beauty as a conduit to human flourishing. Beautiful moments, beautiful thoughts, beautiful actions are not often outcomes we see in strategic plans or logic models.

Indeed, so many of the ways we define and solve problems within social policy and social services sideline beauty or aesthetic knowledge — what we know through our bodily senses of sight, sound, taste, touch, and smell (Stephens and Boland, 2014). My social policy training very explicitly discounted sensory experiences as biased and unscientific. The idea that we ought to pay attention to sensations, to feelings, to movement, to play, to imagination was not in a single policy textbook I was assigned — until I stumbled across a misplaced book on design at the local bookstore. Aesthetic ways of knowing and being are at the heart of design practice. As the authors John Stephens and Brodie Boland put it,

“Design thinking differs from other ways in which the arts and organizations intersect, as its processes are intentionally used to define and resolve a specific problem…In defining the problem, participants create models of the situation or experience through the use of physical materials, or acting out the various processes they hope to change. In designing solutions, participants actually try out multiple iterations on themselves and with end-users, continuously scrutinizing, ‘How does that feel?’ What can you do differently now?’”

Where policy and services are so often steeped in the language of risk & safety; efficiency & effectiveness; right & wrong behaviours, art and design open us up to the sacred, profane, and all the shades of grey. Because that is where life is lived. What I’ve found so powerful about designerly approaches to social problem solving is that, when rooted in a critique of power, they start by embracing human needs and desires — not as systems define them, but as people themselves do. It’s messy. But in the messiness, it’s often alive, and in that aliveness, it’s often beautiful.

Our guest contributor this week is my favourite thought & action partner, Gord Tulloch. Gord is the Director of Innovation for posAbilities, but, really serves as its resident philosopher. He is one of the few leaders within a big social service to not only extol the value of beauty, but find creative ways to resource the pursuit of beautiful moments, thoughts, and actions. His insistence that beauty and flourishing are intimately interconnected lays the groundwork for so much imagination and experimentation.

What is beauty?

Philosophers and psychologists usually talk about three different kinds of beauty: aesthetics, such as music and art, natural beauty, which we experience out in nature, and moral beauty, which is when people perform moral acts of compassion, courage or selflessness. Some also talk about a fourth category, which is the beauty of ideas.

Wisdom-seekers and ancient cultures have been trying to make sense beauty for millennia, and it still evades understanding. Nevertheless, here are a few themes that consistently surface:

Unity in diversity. This is the sense that beauty involves a harmony among diverse parts. It’s about wholeness and balance amongst dissimilar things, whether they are colours, musical notes, people or ecosystems. I really like the language that Roxanne Lalonde uses—beauty is “unity without uniformity and diversity without fragmentation.”

Disinterest. This may seem counterintuitive, because obviously we are very interested in beauty, but what it means is that when we encounter moments of beauty, the self or ego is no longer preoccupied with itself and its own concerns. Nor is it thinking about how it might use, control or profit from whatever it finds beautiful. When we encounter beauty, we momentarily forget ourselves. We are enraptured by something else, a something that rushes in and fills us, and it is as if our worries and self-interests momentarily flow out to make space.

Transcendence. Philosophers and social scientists often talk about beauty in terms of transcendence, which is this sense of slipping outside oneself, one’s ego and physical limitations, and into a deeper awareness of a larger unity. So we can see how this could relate to the other two themes. In moments of transcendence, we are no longer discrete and solitary beings, we are part of something larger, something unfathomable, a greater harmony. This is why this experience often has spiritual and mystical interpretations, though it doesn’t require them.

So what does beauty “look” like…

Too often, we think of beauty as something to do with the exteriority of things. Advertisements are usually about aesthetics: sleek cars, elegant kitchen designs, exquisite jewelry. Sometimes, people are reduced to merely beautiful things, to attractive surfaces, wrapped in other attractive surfaces, like fashionable wear or cosmetics. And so, beauty becomes commodified and associated with materialism and superficiality, or to certain narrow ideals of femininity or form. It’s no wonder that the “cult of ugliness” (first coined by Ezra Pound) arose as a protest against classical aesthetic ideals, especially as they were developed and expressed in modernity. What a society deems “beautiful” is too often narrow and leaves out much of the world’s diversity. But the things we don’t find beautiful are usually the things we haven’t looked at closely enough, or that we’re too prejudiced to see.

Beauty is more than pleasing sights and sounds, however. It is a portal to a world of interiority, to meaning and significance. A beautiful story or song can bring us to our knees (or to the tips of our toes!) and cause us to feel instantly connected to others and to the human project. Dipping our bare feet into a river, or gazing up at the stars, may remind us that we are part of nature or a vast, unfolding universe. It may also stir a sense of being connected to a deeper essence, whether it’s a life principle, or love, or the divine. Beauty is more than sensory pleasure or enjoyment; it is where we come alive.

Okay, but what practical good is it?

Even were it not about meaning and significance, or perhaps, because it’s about meaning and significance, encounters with beauty produce many beneficial effects. These include:

positive affect (e.g. cheerfulness)

respect and wonder

friendship and social engagement

intrinsic aspirations

generosity

vitality

cognitive abilities and concentration

open-mindedness

sense of relatedness

gratitude

hope

love, empathy, sympathy

trust

self-actualization/self-transcendence

If we are interested in good and full lives for the people we support, and for our friends, families and ourselves, then we need to pay attention to beauty. But if we only seek beauty for its effects, then we will have failed to understand it altogether.

Beauty changes how we show up in the world

Plato said that love and beauty are related because we love what we find beautiful, and we see beauty in what we love. Beauty therefore inspires us to take better care of others and the world around us, because we take care of what we love.

And this bears out in experiments. When we encounter moments of beauty, we act differently. We are more likely to engage in pro-environmental and pro-social behaviours. Spending time in nature—or even just viewing some photos or videos of it—makes people much more likely to engage in environmentally sustainable behaviours. Noticing acts of compassion, kindness or generosity is more likely to result in us being compassionate, kind or generous ourselves.

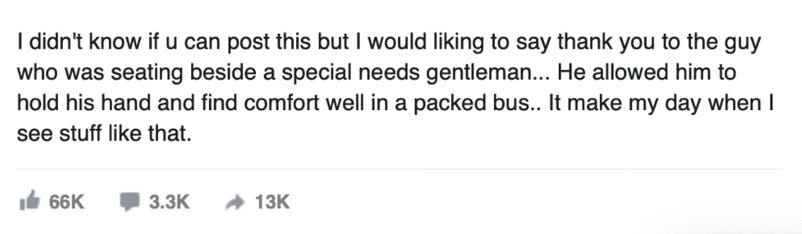

In 2015, Godfrey Coutto was a young McMaster student in Hamilton, Ontario. Robert, a Deaf person with a developmental disability, and a stranger, came up to him on a city bus and shook his hand. Only, he didn’t let go. He sat down beside Godfrey, who eventually put his arm around him.

Another commuter captured the moment and posted it on Facebook:

Beauty can leave us breathless. It can expand our chests and catch in our throats, and perhaps moments of moral beauty most of all. They inspire us to want to emulate the beauty we see in others.

Of all the human emotions, there are only two that enable us to transcend ourselves: appreciation of beauty, and awe. In those moments, we are transfixed by something outside ourselves. We are swept up in something so extraordinary and amazing that we lose sense of ourselves, we matter less or not at all. And when we return to ourselves, we are changed. We are better humans. Better stewards of the earth. Just better.

Beauty invites us to become humbler and more curious; less selfish, judgmental, and transactional. It reveals a relatedness that we might not feel, because we are too caught up with being singular individuals. Fragments.

Beauty teaches us that the world, and everything in it, is sacred.

…There is such a thing as an Indian aesthetic, and it begins in the sacred.” - Victor Masayesva, Jr., Hopi videographer.

So what does this have to do with community living?

Our sector tends to be preoccupied with that is happening on the outside—skills, activities and behaviours. This is the world of surfaces, not meaning. But meaning is where life is lived. How do we get better at addressing soul-needs for purpose, love, hope, creativity, reflection, and importantly, beauty?

We also tend to focus on social inclusion, as though that is the only way to belong to the world. But beauty shows us that we are part of something bigger, too. We are part of a human story that goes back tens of thousands of years and that is lived afresh by billions of people around us. We are part of nature, too, her cycles and rhythms, and in relationships with the rivers and lakes, grasses and trees, foxes and birds, and planets, moons and stars. We are part of something glorious (which literally means, “great beauty”). And surely that’s important, too.

Perhaps our purpose in life, which includes our work, is to notice and cultivate more moments of beauty, because when we do, everything both expands and falls into place. Everything is better.

Walking in Beauty: Closing Prayer from the Navajo Blessing Way Ceremony

CONCEPT RECAP

What is beauty?

While the definition of beauty is debated, it’s often included as part of a set of ultimate values alongside truth and goodness.

The classical idea of beauty — as presented in Renaissance paintings & architecture — is symmetry, harmony, and perfect proportion. All the parts are arranged in a coherent whole.

Other traditions look at beauty as that quality that brings forth love, passion, and longing.

What’s the rub?

Feminist and marxist critiques of beauty point out the shadow side: the way in which ideal standards of beauty oppress and exploit women and the working class.

Social policy and social services tend to see beauty as superfluous and unpragmatic. It’s perceived as irrelevant to meeting people’s basic needs.

Is there an alternative framework?

Yes! The writer & philosopher Elaine Scarry connects beauty and justice. She (and others) argue that beauty is aliveness. Beauty de-centers us, leads to care, inspires us to bring other beautiful things into existence, and provokes deliberation, amongst other things!

Why does beauty matter?

Beauty is at the heart of being human.

In the idealist tradition, “the human soul, as it were, recognizes in beauty its true origin and destiny.”

Beauty and awe make a measurable difference to wellbeing.

How can you apply this idea?

We can all hone our awareness of beauty by quite literally stopping to smell the roses — and taking note of what feels alive, resonant, and moving around us.

We can bring art and design methods into solving social problems

We can craft policies & deliver services in ways that recognize beauty as a valuable means and meaningful end

Want to read more?

Stanford’s Encyclopedia of philosophy has a helpful post about beauty, which is cited here!

Nancy Perkins Spyke offers a helpful (and slightly more accessible) summary of Elaine Scarry’s work on beauty and justice

John Paul Stephens and Brodie Boland write about the value of design in organizations