My mom is a therapist. People often ask what the experience was like — was I endlessly psychoanalyzed? Not endlessly — though we did play therapeutic board games to practice sharing feelings! My most enduring take-away is a big idea: humans are capable of growth and development. Without the possibility of self-directed change, therapy is pretty moot.

Now, as a new mom, I am confronted with just how much change is the base state of existence. As I write this, I am watching my little one teach herself to stand and retrieve the toy she wants. Last month, she needed help to sit. This month, she crawls and foists herself up in pursuit of all that is bright or shiny, dirty or dangerous. Curiosity and desire spur near constant change.

While we, as a society, believe children have the capacity for change, we are far more skeptical of whether adults, especially adults on the margins, can change. So many of our social policies and services are built on the presumption that adults do not change - at least not willingly. Threat, shame, and punishment are assumed to be more effective at driving behaviour than curiosity and desire.

I cut my policy teeth as a 10-year old sting agent for the Texas Department of Health busting store owners for selling cigarettes to minors. Cue embarrassing video below. When that didn’t stem youth smoking rates, lawmakers tried to penalize adolescents for the possession of tobacco products. Ten years later, as a policy analyst with the UK’s Ministry of Education, I wrote briefs on how to reduce the number of young adults not in education, employment or training by ticketing parents, making benefits conditional, and imposing greater oversight on their day-to-day activities.

How systems treat behaviour

Rather than see behaviour as malleable, too often our systems treat “challenging” or “problematic” behaviour as a fixed identity; a scarlet letter that shall forever alert others to the risks the person poses. People with bad credit histories are branded hard to house. Adults who have served time are branded convicts in future job applications.

During an ethnography of a mum embroiled in Australia’s child welfare system, I watched as a social worker dismissed her desire for travel as just another unrealistic goal, validating a pattern of “irresponsible” behaviour. During my first months in Canada, I shadowed the parents of a young man with autism who were desperate to qualify for government support. During the intake visit, they intentionally provoked their son’s “aggressive” behaviours knowing that these behaviours would permanently mark their son as “high needs” and unlock greater resources.

A core tenet of narrative therapy is the problem is the problem; the person is not the problem. Across pretty much all of the policy areas I’ve worked — be it addiction, child protection, criminal justice, disability, domestic violence, homelessness, or unemployment — we started with the opposite precept. People are defined by their “anti-social” behaviours — and people with these “anti-social” behaviours are a problem. One function of disability, health, housing, employment, and family services is to manage at-risk people, and where we cannot contain their ‘risky’ behaviours, to compel change.

No doubt that sounds harsh. Most of us enter social policy and social services with a strong helping inclination. We are motivated to ensure people are supported and cared for.

But, the helping business is different than the change business. And mandated change is different than self-directed change. So much of our understanding of behaviour is rather rudimentary. Sticks and carrots.

Systems tend to default to a narrow set of behaviour change strategies: incentives and persuasion, and if that doesn’t work, restrictions and coercion. But, our behaviour — what we do and say, which is underpinned by what we think and feel — is shaped by a vibrant landscape of social, psychological, physical, and environmental factors. Understanding those factors can help us to make better social policy and services. Appreciating our relationship to an always changing interior and exterior landscape is key to co-designing transformative policy and services. That is, social policy and services that foster flourishing. Stay with me — I’ll get to the difference.

Where theory can be useful

So much social practice lacks evidence. Theory is often the missing ingredient of intervention design, argue Professors Susan Michie, Maartje van Stralen and Robert West in their paper: The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterizing and designing behaviour change interventions. While theory can sound terribly academic, it underpins much of what we do. A theory is simply a set of assumptions guiding action — if we do x, it will lead to y. And yet, when we fail to make our theories explicit, we risk operating under incorrect or incomplete assumptions. They write:

“Interventions are commonly designed … with no formal analysis of either the target behaviour or the theoretically predicted mechanisms of action. They are based on implicit commonsense models of behaviour. Even when one or more models or theories are chosen to guide the intervention, they do not cover the full range of possible influences so exclude potentially important variables. For example, the often used [models] do not address the important roles of impulsivity, habit, self-control, associative learning, and emotional processing. In addition, often no analysis is undertaken to guide the choice of theories.”

Michie, van Stralen and West bring together 19 behaviour change theories into what they call the “behaviour change wheel” to guide effective intervention design.

At the hub of the wheel are three interlocking factors necessary for people to change their behaviour: capability, motivation, and opportunity. (Fun fact: under US law, means or capability, opportunity, and motive are prerequisites for finding a suspect guilty of a crime). The second layer of the wheel includes nine components of behaviour change interventions. The outer layer of the wheel are policy levers. When we put it all together: People need knowledge & skills to perform a new or different behaviour. Modelling, training, education, and persuasion are common interventions to impart knowledge and skills. People also need a strong intention to perform the behaviour. Here, incentives and coercion are oft used intervention types. And they need an environment that facilitates, or at least does not constrain, the target behaviour. Restrictions, enablement, and environmental design are possible intervention categories. These interventions can be codified as guidelines, operationalized within regulations, written into legislation, incorporated into budgets, implemented as part of service provision or woven into marketing plans.

Within the capability, motivation, and opportunity trifecta, we can get even more granular. To change our behaviour, we need to hone our physical and psychological capabilities. If we want to exercise more, for example, we might need to move our body in different ways. To learn some different ways of moving our body, we may need to comprehend verbal or visual instructions, or remember a pattern of actions. Then, there’s our motivations. How deep is our desire to exercise? What we want is shaped by our feelings and impulses, associations, and innate dispositions (automatic processes) and by our thoughts, plans and goals (reflective processes). But, none of us exist in a vacuum. Whether we can act on our needs and wants, or practice our skills, is dependent on the physical opportunities in our environment (do we have access to a place where we can move our body?) and on our social & cultural context, which exerts influence over our needs and wants.

Needs and wants are powerful change propellants. As West and Michie summarize in their Brief Introduction to the COM-B Model:

“The fundamental principle of human behaviour [is] that at every moment, we act in pursuit of what we most want out need at that moment. When attempting to change behaviour by changing motivation, a key target is the momentary wants and needs that will be experienced at the moment when the behaviour becomes appropriate.”

Opportunity and capability act as gates.

“They need to be open for motivation to generate the behaviour. The greater the capability and opportunity, the more likely a behaviour is to occur because the more often the ‘gates’ will be open when the motivation is present.”

Behaviour change, then, requires motivation, capability and opportunity to work in concert. Policies and services tend to focus on one factor over another. Capability is a favoured factor. The thinking is: if only people knew better, they would do better. If kids only knew drugs were addictive, they wouldn’t do them. If folks who were unemployed knew how to write a resume, they would get a job. Indeed, most of the interventions I reviewed as a policy analyst fell into two categories: (1) those focused on care, not change, and (2) those focused on changing “problematic” behaviours via information delivery and skill building.

How we use behaviour change theory

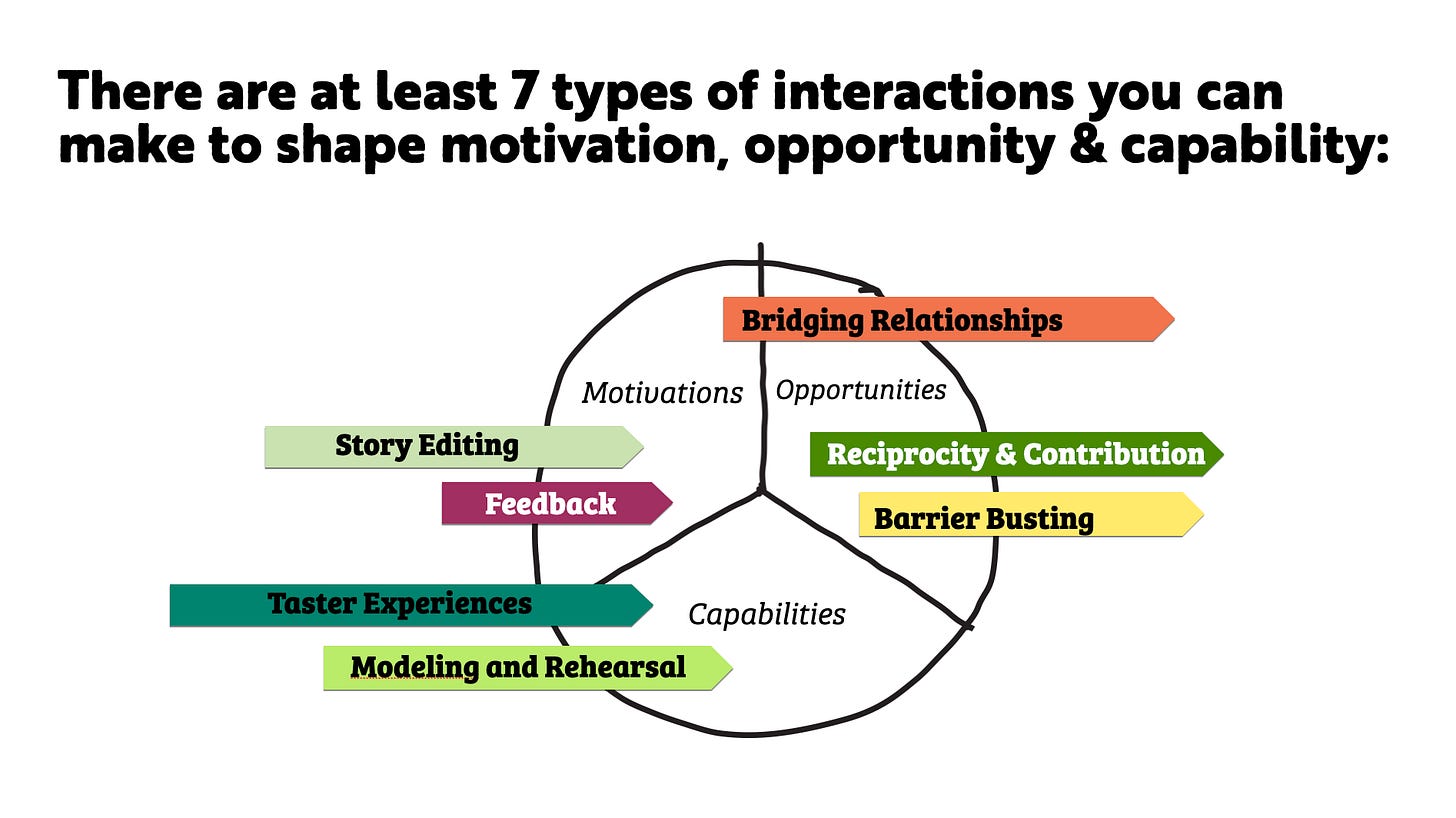

To offset these defaults, InWithForward’s design practice emphasizes self-directed change and uses the wheel (in combination with what we call the 7 mechanisms of change) to co-design interactions that creatively bring together motivation, capability, and opportunity. Much of what we make and test are novel opportunities to quench existential needs, stoke desire, and practice different capabilities.

For example, at a busy-in drop-in centre in downtown Toronto, we prototyped a range of COM-B interventions. As folks entered the space, they were invited to choose a mug to reflect their desire for change in that moment. Orange cups expressed a strong motivation for action. Blue cups expressed a desire for rest. Yellow cups a desire for distraction. Different coloured cups sparked different kinds of conversations with staff — and opened-up alternative physical spaces (a quiet space versus a space for making phone calls and accessing peer support) and capability building opportunities (a meditation experience and an unlearning addiction workshop). What behaviours people wanted to change, we intentionally left open.

But, even good theory has oversights

Over the years, as we’ve up-skilled service providers and policymakers to use the COM-B framework, we’ve seen a tendency to uncritically set target behaviours. This is an oversight of the COM-B framework, which does not address who should determine which behaviours to change. One of the hallmarks of the modern welfare state is the way in which it gives precedence to basic needs, invisibilizes existential needs, and sidelines, if not holds contempt for, desire. What people want is perceived as a luxury!

In workshops, we’d watch as policymakers and providers placed behaviours around seeking employment and housing at the centre of the wheel — even where we introduced ethnographic research indicating people’s need for purpose, connection, and control was as important as their need for income and housing. Rather than view jobs or housing as important opportunities for finding purpose and building social networks, they became the target behaviours and measurable outcomes, even if they turned out to be dead-end jobs or crappy housing situations, which stood in the way of people’s sense of control or connection.

As behaviour change theories have entered popular parlance, policy discourse, and service design, its contortions have come into view:

Target behaviours set by experts and professionals

Treating behaviour change as linear & permanent; controllable & fully measurable

Seeing individuals, rather than individuals in relationships, as the primary unit of change

Let’s return to my home ‘laboratory’ for an example. Not only is my ten-month old continually exhibiting new behaviours, she is also cycling back to old behaviours — what child development experts like to call regressions. For the last week, she’s seemingly forgotten how to fall asleep on her own — even though independent sleep was a behaviour she learned and mastered for over six months! If sleep was the target behaviour, and today you evaluated her progress, the outcome would be pretty sub-par. But, if novelty-seeking or sociability were target behaviours, and sleep was construed as an environmental factor, you might come to a different conclusion: that sleep was a rather insignificant variable in her willingness and capability to learn new things, but quite a significant factor in my willingness and capability to learn new things today.

When our systems set their sights on a particular behaviour, without zooming out to appreciate the wider context, we can miss what truly matters, or worse, impede sustainable and volitional change. That’s the thing about most of the ‘problematic’ behaviours that are the focus of social policy — be it addiction, crime, unemployment, aggression — they can’t be changed in stealth, without people’s buy-in and commitment. Agency and behaviour change go hand in hand.

At the same time, simply saying individuals ought to set their own target behaviours misses how systematized most of us are. Nearly all of us are products of school, family, government, and religious systems, which have shaped our needs and wants. This is especially true for people entrenched in social care —such as foster care, criminal justice, or disability services — where the story of self has, too often, been determined by assessments, risk matrixes, case notes, safety plans, critical incident reports, and more. Asking people to select the behaviours they want to change can, at times, affirm the system’s narrow point of view. None of us know what we don’t know. Until we’ve been exposed to a range of possibilities, and had the opportunity to reflect on our needs and wants within different relationships, we aren’t able to meaningfully exercise our agency. And without the space to exercise our agency — to not only explore, but pursue our wants and needs — we cannot flourish.

Of course, part of exercising agency might be choosing not to change.

Balancing change and acceptance

Recently, we’ve started to question what a relentless focus on change may overlook. When we look only for change, we may fail to see the role acceptance plays in a flourishing life. Acceptance, as opposed to resignation, is coming to terms with our present realities. It is isn’t giving up or stagnating. It’s about being fully present, open to whatever the moment might bring. We see this most clearly in our work with Curiko, where we’ve moved away from defining good outcomes in terms of behaviours like employment and independence. Instead, we try to create the conditions for people to share a moment of connection. Sometimes, moments spark a shift in people’s motivation or capability, or unlock future opportunity. Other times, moments are one-off. Community members have told us how freeing it can be to simply be present — to be freed of staid routines and the pressure to set goals, make plans, and evaluate progress — and not have to do or be anything other than what one feels in the moment.

That sense of freedom and possibility that comes from being fully engaged in the present resonates. Of all the early trials and tribulations of motherhood, learning to be in the moment, whilst also in the throes of constant change, feels both hard and meaningful. Flourishing is very much a balancing act. To design social policy and social services that enable flourishing, we must continually experiment with how to balance care and change, change and acceptance, intentionality and emergence, individuals and relationships, basic needs with existential desires, and capability building with opportunity making.

What does change look like in your context? Check out this week’s prompts, and join us for an open practice call Thursday, May 1st from 2:30-3:30pm PST on this zoom link.

CONCEPT RECAP

What is Capability-Opportunity-Motivation?

A compilation of 19+ different behaviour change theories.

A framework for understanding what shapes human behaviour, and how to design interventions to change behaviour.

At the core of the framework are three factors: capability, opportunity, and motivation. Our behaviour is the product of what we want & need (our motivations), our knowledge, skills & physical abilities (our capabilities), and our social, cultural & physical environments (the opportunities around us).

What’s the rub?

The framework does not address who gets to choose the behaviour to change, and the way in which systems can exercise power and control over people.

The framework also does not make explicit that change is rarely linear or permanent, and can lead to unrealistic expectations and metrics.

Is there an alternative framework?

We can apply a critical lens to behaviour change frameworks, and design interventions that enable people & professionals to examine needs, wants, and ideal behaviours.

We can see behaviour change as one means towards a flourishing life, but not the end in and of itself. A flourishing life is not only a life of growth & development, but also of acceptance & presence. We flourish when we use, develop, and enjoy our human capacities for love, connection, learning, meaning, purpose, etc.

How can you apply this idea?

You can reflect on how behaviour is defined in the context of your work: what is seen as good versus problematic or risky behaviour? Why?

You can surface the assumptions about behaviour change in your work. Who is seen as capable of change? What brings about change?

You can try using the COM-B framework to analyze the work you do: what are the target behaviours? How do you shape motivation, opportunity, and capability?

You can ask questions about who ought to choose the target behaviours, why, and how.

Want to read more?

Here’s a brief introduction to the COM-B framework

Here’s the COM-B framework website with plenty of examples

Here’s our 7 mechanisms of change paper