We’re living at a time when this Robert Burns quote feels especially true: “The best-laid plans of mice and men often go awry.” How, then, do we iterate our way forward? Join us tomorrow at 2:30pm PST on this zoom link to hone our collective capacity to iterate, and keep reading to reflect on how iteration shows up in your own life.

I am a recovering perfectionist. As a freshman college student, I cried on receipt of my first ‘B’. So, what a strange turn of events to find myself in a career predicated on embracing missteps and failures.

It was a misstep that led me to discover design. I took a wrong turn in a bookstore, found myself in an unknown section, picked up a book that I couldn’t put down, and, within months, deviated from my carefully crafted linear life plan. Up until that point, I had learned — and deeply internalized — that good work, and a good life, came from rigorous planning and faithful execution. You dream it. You build it.

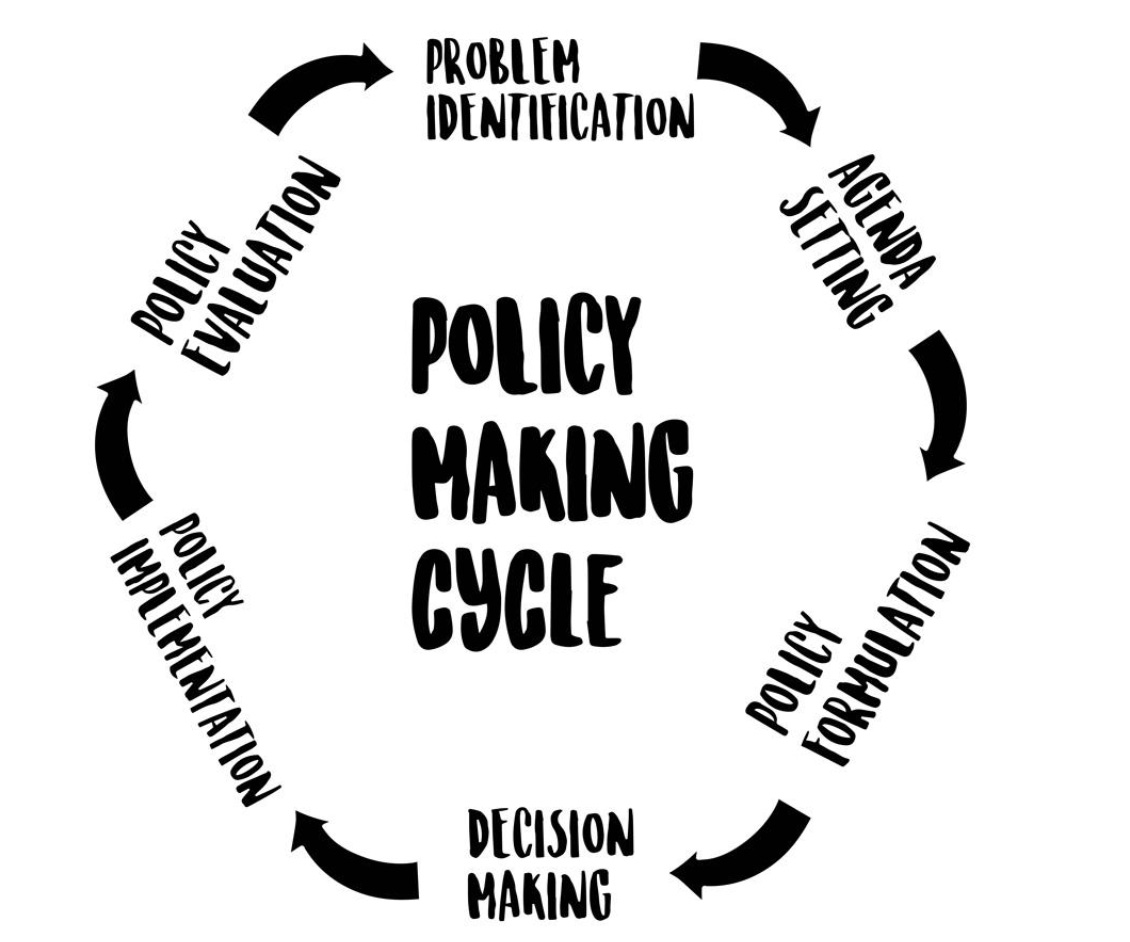

Indeed, over most of my schooling, I was trained to think that social problem-solving was an orderly six-step process: identify the problem, gather experts to set the agenda, formulate policy options, decide between options, implement the best option, evaluate, rinse and repeat.

And yet, try as I did to follow the cycle, I kept getting stuck. No matter how many articles I read or datasets I pulled, problem identification always felt problematic. Who should name and frame problems? When a city asked for my help to address low attendance at their youth centres, I took the problem as a given and skipped ahead to policy formulation and decision-making — only to find at policy implementation that young people had a very different conception of the problem: lack of autonomy and control. By that point, all the resources had been spent, and we were stuck delivering a policy for the wrong problem.

So it was nothing short of revelatory to encounter design and its foundational principle: iteration.

“The iterative and synergistic interplay between creation and evaluation is the basic process of design found in all creative fields. The iterative process (creation-evaluation-creation-evaluation) is continued until the result is sufficient, or until resources to continue development are exhausted.” Link

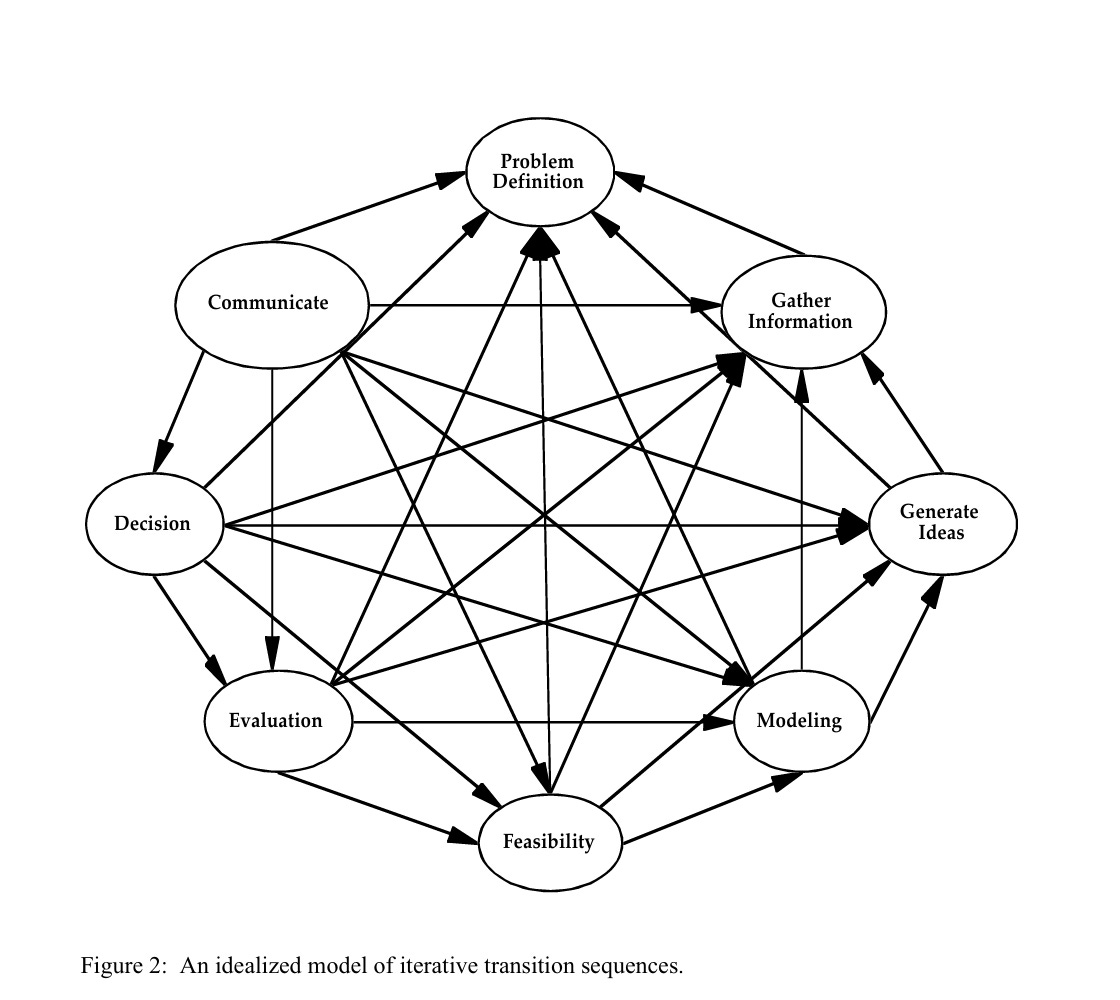

In other words, rather than identify a problem, develop options, make decisions, and implement, we might surface hunches about the problem, generate and test ideas on paper, revisit the problem, make a small scale model of the solution, and based on the learning, recast the problem, again.

Here’s what an iterative problem-solving process looks like:

Iteration is distinct from editing. When you edit a paper, for instance, you work from a mostly complete draft. The goal is to improve your writing: to tweak its grammar, structure, style. Iteration, by contrast, eschews completion. You make and evaluate as you go: first creating an outline, testing the waters with a paragraph or two, seeking feedback, creating a next version — perhaps it’s a podcast, not a paper! — and continuing until you get close enough to your desired outcomes — say clarity, inspiration, or provocation.

Creating and evaluating your way closer to a desired state feels quite different than masterminding answers to problems. For one, it honours not knowing. You start somewhere, and through repeated cycles of making and testing, refine both purpose and outputs. Often where you land bears little resemblance to where you started. That’s because iteration opens-up space for spontaneity and emergence, allowing the feedback process (instead of the the initial idea or product) to lead the way. But, oh, can that be painful to do!

Iteration requires that we loosen attachment to our ideas and products, and cede some control to the people engaging with them. We have to be willing to switch vantage points, synthesize diverse perspectives, and discern what might move us closer to a desired state — which may be different to what we were tasked with delivering. Iteration may seem meandering, and yet, empirical research shows that failing early is a better use of resources than implementing something premised on the wrong assumptions or a tepid purpose.

Critical to effective iteration, then, is understanding what is a desired state. What are you testing your idea, product or model against?

Is it about its beauty or attractiveness?

Is it about accessibility or engagement?

Is it about impact: does it shift people’s minds or behaviours?

Is it about viability: the resources it requires to run, or the cost to access?

Over the last few years, I’ve found some of the most helpful metrics for iteration to be around energy and momentum.

Whether the idea or product moves people in some way: does it spark an emotion, stir a sense of connection or resonance, or tap into creative energies?

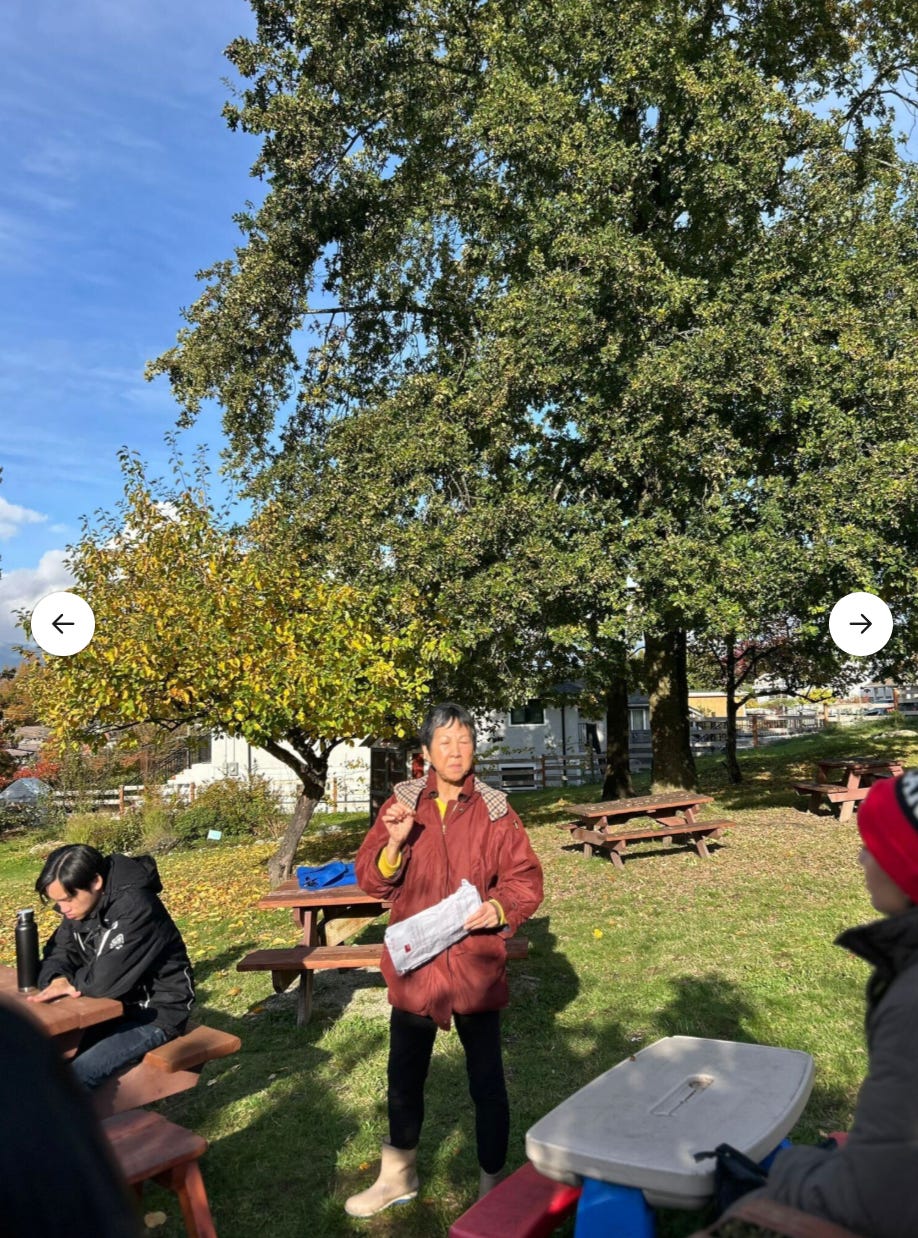

Our team is currently co-designing and iterating a cohort for young people with disabilities on the very topic of iteration! Rather than plan all ten weeks of the cohort in advance — which is what many of us understand to be the professional thing to do! — we’ve making and testing as we go. Alongside our partner organization, Kinsight, we’re exploring the question: how might we enable young people to see themselves as designers of their own life, and embrace a spirit of learning and iteration rather than planning and control?

Starting with a question, not a set of tasks (e.g write a curriculum and run a cohort), is at the heart of iterative design practice. Every week, the team tries out a new framework, tool, and community-based experience — and through dialogue, prompts and debriefs gains a sense of where there’s energy and resonance. That shapes what happens the week after. We don’t know exactly where we are going. And that’s the point. Authentic co-design means giving up on a pre-set destination, and trusting that repeated cycles of making-testing-evaluating will unlock rich learning, buy-in and momentum — which are preconditions for change.

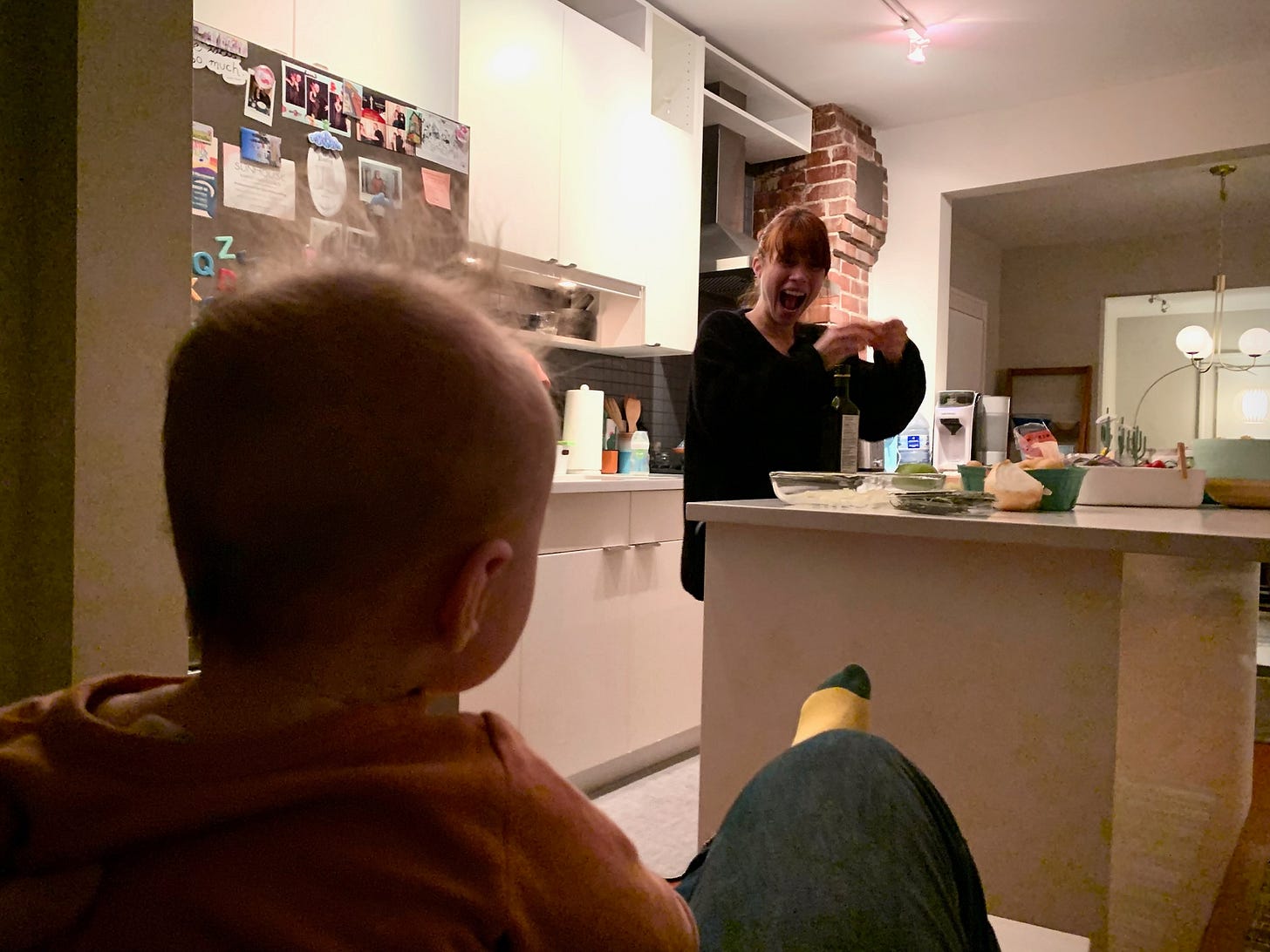

It’s been nearly two decades since I stumbled into that book on design. By this point, I thought I would be de-programmed from linear thinking: from the notion that you can simply plan your way to a preset destination. Then I had a baby. And realized how deeply I’ve been socialized to exert versus cede control. Before I gave birth to my little one, I read blogs on how to create predictable rhythms and routines for you and your baby. But, once Lilah arrived, not one of those preset schedules played out as the blog suggested. The more I tried to contort our days to fit my plan, the more Lilah resisted.

As soon as I let go of the plan, and started asking curious questions — When are Lilah and I in sync the most? What does it look like to be ‘in flow’ with each other?’ rhythms and routines started to form. None of these rhythms and routines unfold in the same way from day-to-day, but time has started to take more shape and form. As my partner constantly reminds me, our little one isn’t a robot we can program, but rather a tempestuous human we must learn how to be in relationship with. Leave it to him, someone in the creative industry, to bring me back to the necessity of constant iteration.

What are you iterating in your personal or professional life? Is there any question you are holding that you are making & testing your way towards answering? If nothing comes to mind, that’s OK! Where do you experience the rubs between planning and iteration?