How do we grapple with a life full of love and loss? Ruth Ann Linklater and Dr. Renee Blocker Turner are trained counselors who are also finding beautifully personal ways to blend spiritual and somatic approaches to healing. Rather than speak in the abstract, both Ruth Ann and Renee vulnerably share their own experiences navigating grief & loss, and what it means to hold space for others to do the same.

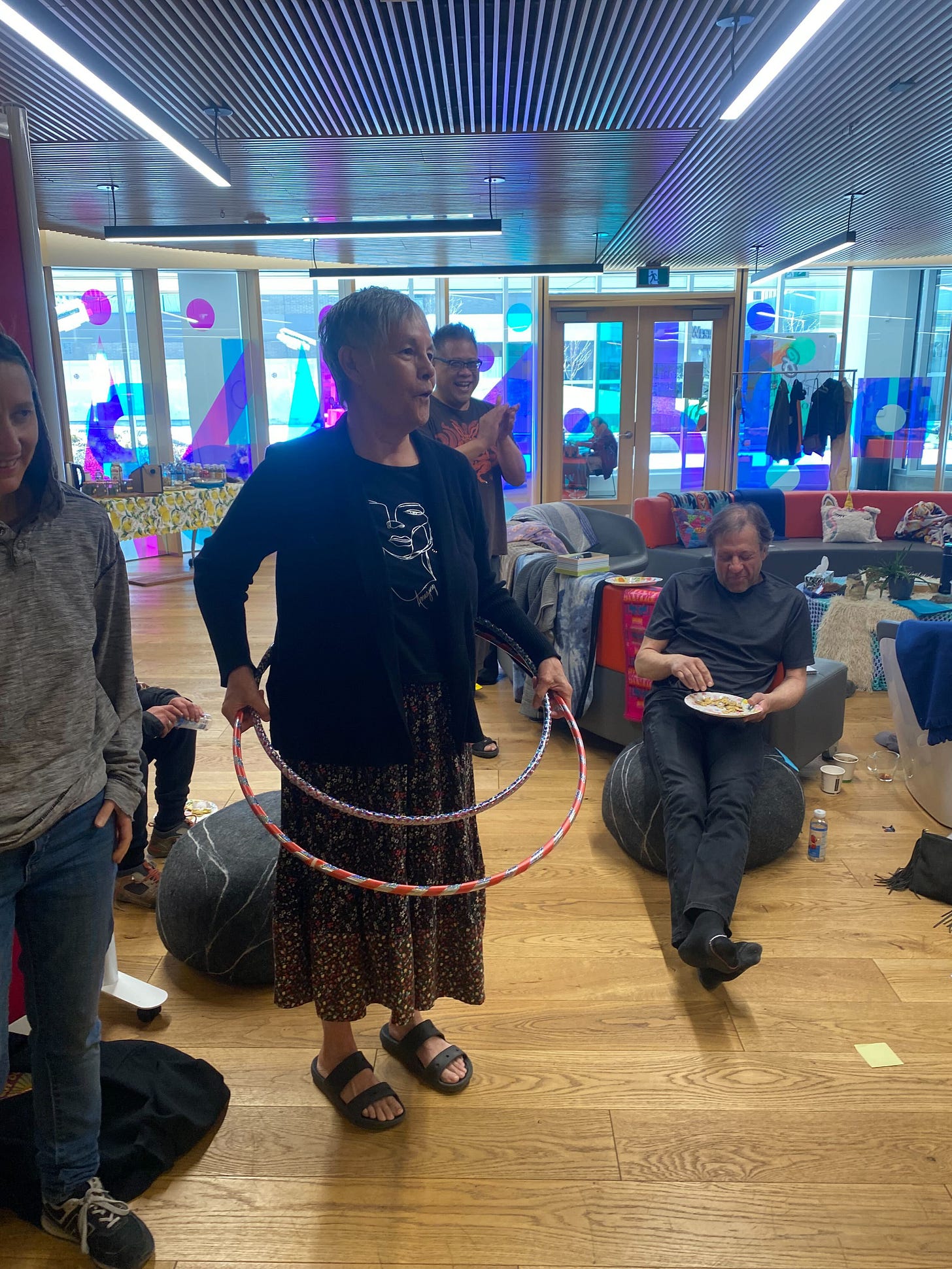

Ruth Ann Linklater bridges worlds. As a marriage & family therapist, member of Couchiching First Nation, mom, grandmother, sister and aunt, Ruth Ann bridges therapy and ceremony; faith and spirituality. She supports Soloss as a very valued cultural advisor.

Dr. Renne Blocker Turner is Core Faculty with Walden University teaching graduate courses in clinical mental health counseling, alongside running her own clinical practice. She is particularly interested in utilizing and teaching non-traditional healing methods. Together with Sarah Stauffer, she co-edited the book, Disenfranchised Grief: Examining Social, Cultural, and Relational Impacts.

Part I: In conversation with Ruth Ann Linklater

Q: Thanks so much for taking the time to talk about your experiences of grief and loss, Ruth Ann. It’s a big and weighty topic, but I am going to start with something a little silly. How would you introduce yourself to an alien?

Ruth Ann: Wow, well I would be quite surprised and quite curious. I’d say, ‘Oh, I’ve never seen you before. I’m wondering where you came from?’ If the alien was cute, I’d tell them that. Would we speak the same language? Would we understand each other? I would say, ‘I’m so glad for your visit. I don’t know how long you are going to stay, but thank you for coming.”

Q: Today we are talking about ‘G is for Grief.’ And I wonder if you would mind sharing your relationship to grief and loss. Please share as little or as much as you feel comfortable!

Ruth Ann: I've had a lot of grief in my life. A while back, we had a prompt through Soloss to write down your experiences of grief. I think I hit over 200 things. And not to minimize the grief and the loss, but I also added an equal amount of joy or gratitude for things in life that made me happy or smile. It wasn’t about diminishing the grief I’ve experienced, it was about thinking about the big and little things together. It was a good exercise.

My dad passed away when I was five years old. He was 39, so he was a young man, and he left my mother alone with seven children. My brothers were the oldest, maybe 16 or 18. I didn’t really attend to that grief until I was an adult. Then, I think around 2009, I went to a grief workshop to specifically look at the loss of my dad. I consciously started working on that. It took a long time to understand what had happened. You know, sometimes grief goes behind the scenes, it’s not always front and centre, but it is always there. And then at moments it comes to the surface. Like when I got married. Somebody else had to walk me down the aisle. So grief has been with me for a long time.

I try to consciously work at my grief as best I can. I tend to work a lot of my grief out on my own, in my own quiet, reflective way.

I have also lost my oldest son. That loss was so huge, it took over me. It took a very, very, very long time to work through that one. Of course, I am still working through it. A couple of years ago, I knew I had to return to therapy because Christmas was really, really difficult for me. It got better. After he passed, it wasn’t hard every single day. It came and went. For his birthday. For Christmas. So I went back to therapy, and for the last two Christmases it hasn’t been as hard. There was more healing.

And so it takes a long time for different losses. My older brother gave me some traditional teachings on grief and loss, and that's what helped me the most: holding on to and understanding life and death from a cultural and traditional perspective. I really believe my spirituality has helped. Being with the elders and my late friend Leonard Cardinal.

Ten years after I lost my oldest son, I lost my grandson, my late son's son, and of course, that too was incredibly difficult. He passed away at home, and so I tried to help my other grandchildren work through their grief as well. That was good for me too. We went to Jasper for a healing weekend.

Another kind of loss I’ve experienced is having my other grandson diagnosed with schizophrenia. That’s the loss of a “normal life” because I don't think my grandson will get married or have children, but I don't know. I don't know that. I don't know what's in his cards.

Q: You’ve really committed to acknowledging & working through your grief, Ruth Ann. Thank you so much for your openness in sharing. What do you see happens if we don’t work through our grief?

Ruth Ann: For me, I would have continued to remain very sad. I would have continued to have maybe low-grade depression, not really experiencing life the way I want to, and not really being here for myself and my son, my grandchildren, my friends. I think for me, it’s about being able to live again, like, truly live, to feel the strong essence of life. You know, so many of those sayings people tell you -- like, ‘He’s in a better place’ -- are not helpful. People don't want you to be sad. But you need to be what you are.

Q: You’ve drawn on both a therapeutic and spiritual approach to tending to your grief and loss. I know you have a therapeutic background. I'm curious about what each offers. What's different about a therapeutic approach from a spiritual approach? How do they go together for you?

Ruth Ann: Well, I’d say the spiritual approach is much deeper, and takes me to places where I'm not sure the therapeutic does. And I think that therapy offers the space to share my grief, to say it aloud, because you know a therapist will understand more than the general public right now. I appreciate both. And I think both have contributed to my overall wellbeing.

Q: Would you mind sharing more about your cultural background and what your spiritual practices are?

Ruth Ann: I was raised Roman Catholic. I still use the Catholic prayers sometimes; they come back to me. I follow some of the celebrations. That's one thing I thought about with Mary, Jesus’ mother. I understood her in a different way through my losses. I had more affinity to her.

And then, with my spirituality, that comes from my traditional Anishinaabe background, from Ojibwe teachings. My brother has helped share them with me. It helps me to understand the road of life. It helps me to understand our purpose. It helps me understand my son had a purpose. We all have a purpose. And for whatever reason, his purpose was done on this earth and he went back. The traditional culture of teachings and ceremonies, doing the rituals, have been very helpful.

One of those rituals is the fourth year feast. We have a feast four years in a row after someone has passed. We feed them four years in a row. For my son’s feast, I actually felt joyful inside. And then with my grandson’s feast, I felt the opposite. And so I went back into therapy, and I was part of a group that looked at my son, my grandson, and my other grandson with the diagnosis.

Q: Thank you for sharing these meaningful rituals and practices with us. In my own faith, Judaism, ritual is also such an important part of marking loss. Given your strong spiritual and therapeutic practices, where does Soloss fit into the picture for you?

Ruth Ann: Actually my son Robert was in Soloss before I was, and he would talk about it, and share his role as a Losstender. About a year ago, I was talking to Hayley (the Soloss Lead) and Robert, and we decided that I would come on as a cultural advisor, to provide traditional guidance. And I really like that. I really like us to acknowledge the spirits of this land, of what is called Canada, to honor them in ceremony.

When we move forward with things, whether we have been born on this land or not, it’s important to acknowledge the spirits that are here. That's my understanding. It’s honouring the trees, birds, rivers, earth, and the traditional languages of this land.

I think they appreciate it when they hear the language, whether it's Anishinaabe or Lakota or any of the languages across this land. So I bring that into Soloss -- just acknowledging the non-human beings, all the beings, because they are here to help us too.

Q: I wonder what are some things you are learning about grief and loss?

Ruth Ann: Well most recently as part of Soloss, I have been sitting in circle every Friday at George’s House (a hospice). I have been trying hard to listen at a deeper level. To be a witness to whatever is being shared: whether it's the Losstenders or the Sharers, whether they are stories of loss, grief, or joy. It’s a bit different in the sense that we're not there to provide an answer, and that's really freeing. You know, we don't have to think about what intervention might be helpful. It’s natural and organic. It’s taken me a long time to really understand the word organic, and I like it, it’s relaxing, there’s the full realm of feelings; we support each other. There's traditional teachings about the different stages of life, and so I sit and listen. One of the fellas living there, I spoke to him in the Anishinaabe language. It’s not important whether he understands Anishinaabe because he's probably a Cree man. When my son passed away, there were five different languages that were spoken. I really believe the languages themselves are healing, that there is an essence, and a sense of connection. That’s why I spoke to this man in my language. Because he doesn’t need to know the words, the spirit will understand. It will understand the land that the house is sitting on, the trees outside, and the birds.

Q: What have you come to learn what this word healing means? It's a big word.

Ruth Ann: We can think about healing in terms of a physical injury. If I have a bruise on my arm, every time I bump it or move it, it's going to hurt, but eventually it doesn't hurt so much anymore, and then eventually it just hurts once in a while. So I think that's what healing is as well.

One time I was watching my grandson. He was looking out the window, and I felt really sad about his diagnosis of schizophrenia. But, I'm looking at him, and he's really tall and he's healthy. And I asked myself, why am I so sad? He’s strong. He can move and talk, and he has all these other beautiful attributes. It’s not about pushing the sadness away. It’s looking at things in addition to the sadness.

I think that’s what healing is: you can still have sadness, you can still cry and feel hurt, but you can also feel joy and all the other attributes as well.

Q: That’s a beautiful way to put it. What kinds of losses do you feel like don’t get recognized in Western society?

Ruth Ann: One I spoke of already -- mental health diagnoses. There’s also miscarriages and abortion. Abortion is a huge one because there can be so much shame around it. Other losses include divorce or being on the outside of a family system -- maybe you’re family doesn’t approve of something you’ve done or want to do. There’s other things -- like getting your first scar, or the loss of a physical capability. I had a good friend who couldn’t wear sandals anymore because of her arthritis or polio she had as a little girl. It was a big loss for her not to be able to have her painted toes showing!

Thank you so much for gifting us with your words and perspective today, Ruth Ann.

Part 2: In conversation with Dr. Renne Blocker Turner

Q: So Renee, we ask a little bit of a silly warm-up question to everybody! Imagine that an alien lands next to you and asks: who are you? How would you introduce yourself?

Dr. Turner: I would introduce myself by taking them outside and introducing them to nature, because that's a big part of who I am. Feel this tree! You want to hug it with me? I would want to show them my world. And then get really, really curious about them, assuming that we could communicate with each other. What do you need? Why are you here? I would assume I'm safe if they're sitting beside me! Ultimately I would talk about my work. I was on holiday with my family in Lake Tahoe recently. There are Chipmunks there, which are so stink’n cute. A little boy jumped at the chipmunk and scared it. And so I apologized to the chipmunk. I said, ‘We're not all that way.’ And then an hour later, as we were driving, I saw something that was so beautifully human. And I said, ‘See chipmunk. That's who we really are. We're not all jerks!’

Q: Could you tell us about a week in your life? What makes up your week? What kinds of things are you putting your time and energy into?

Dr. Turner: I recently took a full time academic position for Walden University. I believe in the mission of Walden, and so I'm still onboarding, spending time trying to figure out how to be relational in an online program. And so that has proven to be a little challenging. I also have a little therapy practice that keeps me really busy. I have my son. I am an avid hiker, so I like to get out when I can. And because it's not been too hot in Texas, that fills my time. I also just started a group (it’s in the early stages) for the first responders from the Kerville flooding. I thought how important it would be to meet with first responders and people who are out there, searching and finding bodies, and just having a space where we can be together and support in that. Because it's been pretty awful. I grew up in a town just 20 miles from Kerville, and lived there for a couple of years, so the proximity of something like that happening and having clients impacted is hitting in an interesting way.

Q: What are some of the lenses or perspectives you bring to the work? And, what is the work?

Dr. Turner: The work is love. I think that's ultimately it.

I teach students and people I supervise, and anybody who will listen that you have to love people; you have to love clients. You don't have to like them, but you have to love them, because I don't like everybody either.

That’s a part of my spiritual practice too. Compassion is a big piece of this. My compassion and my being open, models perspective. The work is in body-centered somatic space because that's where the pain is stored. If people could think their way out of a situation, they would have already done it. They don't need to go to therapy. Their pain is not a cognitive problem. There is a cognitive part -- and it's the dissonance it seems your work is about, the crisis of meaning, the fact things just don't make sense. But things don't make sense because they don't feel right.

That’s why I work from a body space. I use expressive arts like sand trays with clients.

Historically, I've worked with a lot of kids, but I now work more with adults … My youngest client is 13 and my oldest is 80 so it really spans the gamut. While I'm not good at a lot of things, I’m very good at just being with people in transition and holding space -- what I like to say is sitting in the suck.

Just sit in the suck. There's something you can do. Just sit and love them. And that's sometimes enough. Sometimes it's everything.

Q: That’s really beautiful. I’ll take that to heart at this moment. I wonder when you first came across the idea of disenfranchised grief, which you’ve now edited a book all about. What was your entry into that as an idea?

Dr. Turner: I came across the concept a long time ago because I worked at the Children's Bereavement Center of South Texas. I started in hospice, and then worked in suicide and homicide. I did my dissertation on survivors of suicide loss using breath therapy, a particular type of breath therapy. And so the concept of disenfranchised grief has always been there. We were surprised that when we were shopping the book around, we only got one denial. We thought we’d get more because we’ve expanded the concept. The foreword of our book was written by Kenneth Doka, the professor who coined the term disenfranchised grief. You know he’s a middle class, older, white guy. When we first reached out, I think he was challenged a little bit by the notion of bringing in social, cultural, and racial discrimination into the concept of disenfranchised grief. That it’s not just grief as an individual experience, but at a community level. He was challenged, but he was also open. Because what people are experiencing is things that they cannot talk about. If there’s shame involved, it is connected to loss that’s been disenfranchised or minoritized. I get tears in my eyes thinking about shame. It is the hardest human experience to not feel enough. And then you pair that with disenfranchised grief, and then it’s too big for you.

On a personal level, I grew up in a small town in Texas. My dad died when I was seven. So just the word disenfranchised grief has always made sense to me. I know what that feels like, you know. And even though it was very hard, I had plenty of privilege. I had my grandmother who was everything for me, who I knew I could count on, who buffered things.

Q: What happens when we don't attend to shame and disenfranchised grief? Why is it important to bring it into the light?

Dr. Turner: Because we get sick. We lose ourselves. We question ourselves. We disenfranchise ourselves. There’s a term called self-disenfranchisement that is real. We could say we gaslight ourselves. Because if the shame isn’t held, then there’s no way to organize it.

One of the ways I describe my role to new clients is that I'm like a professional closet organizer, but for emotions. Because if we look at the attachment literature, that's what a healthy attachment figure does, they help organize our feelings, right?

They organize what's happening-- like your new baby, Sarah, whenever they hurt themselves, they are not even really hurt usually, right? But the experience is so big and you're organizing their experience so that they know what to do with those feelings. In the case of shame and disenfranchised grief, there's no one there to organize what's happening. You can't make sense of it, and so you just sit in the heaviness.

I have a client and the things that have happened to them are movie worthy. Like, surely this only happens in the movies, right? And to be with people as they are sharing their experiences, they are constantly checking you out to see if it’s too much for you. They are wondering: Am I too much for you? Is this going to hurt you? And all of that is woven into their narrative of self worth, about goodness and grief. So often people don’t see the grief in their situations because they compare it to other people. ‘My brother had it worse’ type of thing. And so in holding it all, they get sick. We know that if we don’t find a space for the emotions to be organized, where we can let them go, we do get physically sick.

Q: Our team was just talking this morning about how hard it is to make the case to funders that we ought to focus on existential needs -- like the need to feel like we matter. There’s a tendency to just focus on basic needs and ignore the resources required to attend to the whole person and their community. What do you see as the relationship between basic and existential needs?

Dr. Turner: There are now volumes and volumes of studies that have come out of the Adverse Childhood Experience study that tie emotional and physical health outcomes. And physical health outcomes begin to matter to people who have money because of the cost of emergency room visits and the costs to insurers.

Q: We also work a lot in the addiction space. What’s the relationship between grief, loss, and addiction?

Dr. Turner: I think we all know the outcomes of a 28 or 30-day addiction treatment program. They just don’t treat the grief and trauma. In my practice, I see everything through the lens of grief. Grief impacts everybody. I’m not saying it impacts people in the same way, but we all experience it. We have to help people understand that grief isn’t a bad word, that trauma isn’t a bad word, that it’s not a deficit, it’s part of what happens in life … What I know from being a clinician for 20 years and an educator for 15 of those is that people don't want to acknowledge their own problems. They don't want to acknowledge that they have grief and trauma. Often people want somebody to blame. If I can blame it on someone, then I don't have to wrestle with the fact that life is this delicate and fragile. And that anything can happen at any time. It has to be somebody's fault, and that bypasses us from dealing with the existential aspect of it all, from really wrestling with that. So I spend a lot of hours logged with pissed off clients, until they can settle into the disenfranchised nature, into the grief of it, and to the absolute lack of control.

Q: I’ve just noted in your language that you talk about grief and trauma as distinct. You say you work from a grief lens, not a trauma lens. There’s a lot of talk about trauma informed care. What is grief informed care?

Dr. Turner: Gosh, thanks for that question. That's something else that gets me fired up every day.

Grief doesn't always have trauma, but trauma always has grief. 100% of the time trauma has grief. Grief can just be grief.

There are expected deaths. People can have communities of support and healthy attachments. And so when loss happens, we can recognize it as grief. But trauma is so big and so pervasive that it overshadows the grief. From a treatment perspective, when there's traumatic loss, you're working with both at the same time. People are able to do a little bit of trauma work, and then they have to titrate and step down because it's too much, and they'll spend some time in grief work. Both have to be on the table.

Then there’s intergenerational patterns of how grief is processed, and so if a community has not processed, or a family system or a culture has not been allowed to process their grief, then it teaches people what they can't do during grief. And so everything is minimized. There isn’t time to grieve. I don’t have time to work on that because I have to keep the lights on. I have to feed my kids. That’s often where substance abuse can come into the mix. People have to check out in some way from it all.

Q: Thanks for that distinction. How do you attend to trauma and grief differently? What would a grief-informed school versus a trauma-informed school, for example, look like?

Dr. Turner: It’s a good question. There are some specific modalities. With trauma, it’s helping keep people safe when they process it, because it’s really easy to re-traumatize people. I use EMDR and somatic experiencing. It takes time. With grief, I think some people can intuitively work through it. I love the role you’ve created -- the Losstenders -- that’s beautiful language.

There are trauma informed schools, which I think is fantastic, though everything can be turned into a box checking exercise. Unfortunately, I think we often just put a cognitive focus on it. People are often having to retell their narrative. I always tell my clients: ‘Hey, we don’t ever have to talk about what happened.’ It often comes up, but we don’t have to talk about it, the details don’t matter unless they matter to you.

I’ll have to think about what a grief-informed school would look like. It would be heart opening and expressive. So using expressive techniques like movement, music, touch, and writing. Because grief hits us at a deeper level.

Real healing comes from spaces of being able to express and to speak the unspeakable, to somehow express and move through it. That’s why I use techniques like the sand tray. It’s sensory. I can touch my grief. I can touch my pain. I can touch my healing in a way that I cannot do with words.

Q: What do you see as the role of professionals versus everyday folks in responding to grief?

Dr. Turner: I think that more folks, everyday people, should be involved in grief. I don't think there's enough opportunity for them to do that. And I think people hesitate and are fearful of doing that because they have their own unresolved grief. Even other therapists I know shy away from grief.

It’s about showing up. I'm not scared of grief. Often, when things get heavy, we have a tendency to move away or distract, which is very disenfranchising. So lay people still need training around how to do that because our society does not know how to do it. Socially, we do not do well with grief.

Of course, it would be great if I weren’t needed in the community, but I am needed because of all of the social stuff that prevents us from being with grief.

Q: One of the things in the book I enjoyed in the book was exploring attachment and reciprocity, because that's a language that we use a lot in our own work. What does reciprocity have to do with grieving?

Dr. Turner: That’s where understanding comes from, right? In reciprocity, the grief doesn’t have to be equal, but there is some equity in how the grief is shared. There can be some degree of resonance, because we need that to really understand the grief process. Because if not, my belief is that we turn into into a head-based experience, rather than something deeper. There’s a little bit of attachment work that goes into that: how do we tend to other people? I don’t want to steal your own language! I love the language of tending to grief.

The attachment part of that is that there is space for both, that there is some movement, that it's not a one-way grief street. There’s also something about balance, about how you keep your heart open and protected. That’s something I am navigating, especially on harder weeks. A few days after the Texas floods happened, my thoughts went to a client who was supposed to go to a camp nearby two days later. Her campsite was flooded. They were 40 hours from being there. I saw the mom a few days later. And I cried with her. I realized in that moment I was crying for my grief around it all. It wasn’t just me empathizing. I grieved. It wasn’t reciprocal, but it was reciprocated. As in, we were having our own grief experiences at the same time.

Q: How do you personally keep your heart open and in that loving space?

Dr. Turner: Having a spiritual practice -- mine is buddhism -- helps. I do a lot of therapy and retreat work. Most of my friends are therapists. I download as I need to. I’m an introvert so I spend time with myself. I go into nature. I download onto a tree, which is a hundred years old, and it can hold whatever I want to give it. Also having a way to include my body in the process. And as much as I can, practicing self-compassion on those days when I just dropped the ball.

Q: I love the idea of downloading onto a tree!

Dr. Turner: I was recently telling a friend about this practice. And he said: ‘Make sure you ask for permission.’ So now I've been asking for permission, like consent, you know, Can I hug you? I asked my friend: ‘Does a tree ever tell you no?’ And he said, ‘Sometimes. It doesn't happen often!’

Q: Thank you so much for sharing so much and with so much heart!