“Eeeeeeeeek,” my little one squeals at the sight of a big, furry dog a block ahead.

A year ago, I might not even have clocked the dog and his owner. I certainly would not have crossed the street, exchanged names, compared ages of our little and big ones (11 months and 1 year!), or discussed slobber.

This small, seemingly insignificant, interaction made my bleary-eyed morning.

I’m finding this first year of parenting to be a whole jumble of contradictory things — slow and fast, beautiful and messy, awe-inducing and banal, repetitive and emergent, high-touch and lonely.

Little moments of connection have proven to be unexpectedly grounding — an instance of being seen, feeling acknowledged, and stitched into the neighbourhood fabric, but unencumbered by the expectations and responsibilities that come from longer social engagements or ongoing relationships.

The (Canadian born!) sociologist Erving Goffman, famous for using the metaphor of theatre to describe social interactions, would call my little moment of connection, an encounter.

In Goffman’s words, an encounter is:

“When persons are in one another's immediate physical presence…For the participants, this involves: a single visual and cognitive focus of attention; a mutual and preferential openness to verbal communication; a heightened mutual relevance of acts; an eye-to-eye ecological huddle that maximizes each participant's opportunity to perceive the other participants’ monitoring of him.”

In non-theoretical speak, an encounter is somewhere between anonymity and sustained relationship: a moment when people see and talk to one another, literally crossing paths to focus on a topic or object of shared interest.

In a world where devices constantly vie for our attention and earbuds efficiently block spontaneous conversation, face-to-face encounters can feel like a dying interaction type. We’ve become so used to casting our gaze downward at our screens that ‘eye-to-eye’ huddles — where we share a moment of mutual knowing — can feel especially strange. So many of us have been socialized to recoil from the strange and unknown; it’s more comfortable to ignore rather than engage, however briefly, with ‘the other.’

For folks pushed to the margins of our communities, who might look or act differently to social norms, moments of mutual seeing and knowing can be even harder to come by. But, without these moments, there is no possibility for social relationships to form. Loneliness, isolation, and exclusion stay entrenched.

Over twenty years as a professional people watcher (aka an ethnographer), I’m continually struck by how public policies and spaces can make ‘the other’ either invisible or grotesque. Under the guise of public safety, we ticket houseless people on benches and sleeping in parks. We dismantle encampments. We put adults with disabilities in vans and segregated programs. We institutionalize the behaviourally deviant. We engineer our environments in ways where we are unlikely to warmly encounter difference.

Indeed, for all of the language around social inclusion and welcoming communities (language which shows up in plenty of government & non-profit mission statements), most of us have had few opportunities to encounter ‘the other’, on equal ground — not as charity cases or clients, but as fellow humans. And so when we spot someone who walks, talks or interacts in non-normative ways, a lot of us have gotten used to averting our eyes, crossing the street, clutching our bags, and whether we know it or not, expressing discomfort, fear, or sometimes, judgement.

I too feel the pull to disengage. When I am not in ethnographer mode, with an explicit role to get to know others, I notice how habitual it is to avoid the possibility of unease.

How, then, might we re-habituate ourselves to the equal possibility for the surprise & beauty that even brief bouts of human connection can bring? One warm or ‘convivial’ encounter at a time, the researchers Christine Bigby and Ilan Wiesel argue:

“Convivial encounters are marked by friendliness or hospitality, occurring when strangers engage in shared activity with a common purpose or intent, such as tending to a community garden or participating in a community art group. In such convivial encounters, social differences between participants are not eliminated, but exist alongside momentary shared identifications experienced by encounter participants; for example, as community gardeners (Fincher & Iveson, 2008). Over time, the numerous encounters between strangers can produce a “convivial culture” in a city. Social differences, often understood as essential, fixed, and insurmountable identities, become unremarkable compared to these more transient identifications that characterise life in a convivial culture (Gilroy, 2006, p. 40).”

This assumption that you change culture through convivial encounters is core to so much of what we prototype in our social design practice. Over the years, we’ve come to see the interstitial, or in-between space, as especially fertile grounds for moving closer to a culture of wellbeing, which if you had to boil it down, is all about strengthening the relationship to ourselves, each other, land, and spirit. All relationships start with an encounter. Here’s three examples of how we are experimenting with encounters as a way to reinvigorate relationality.

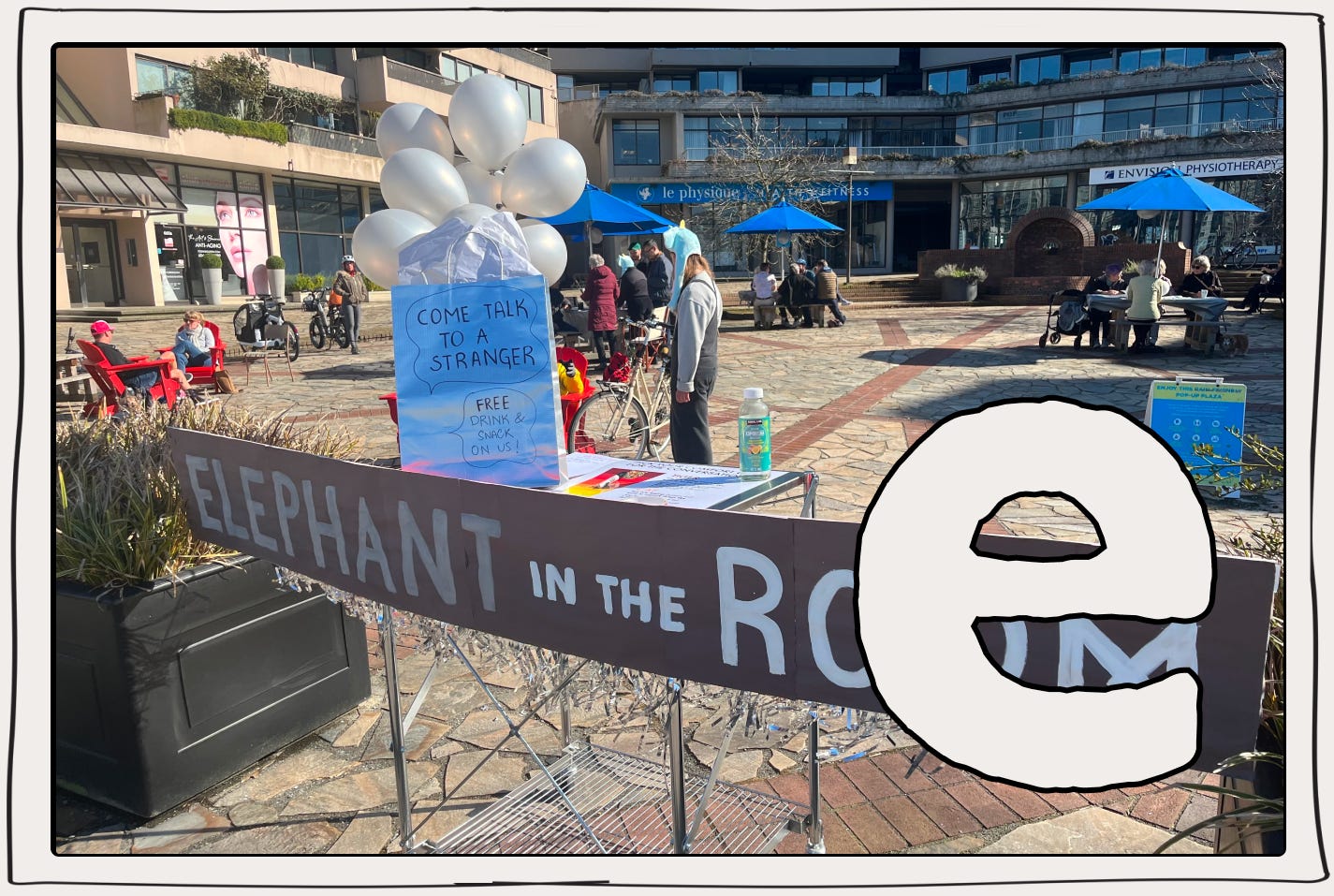

Elephant in the Room is an impromptu public space for deep dialogue across lines of difference. Popping up in local malls and parks, strangers are invited to move past polite conversation by playing with gradated prompts and comfort levels.

Auricle builds local listening infrastructure, training city residents to gather short stories on wellbeing through brief encounters on transit. From offering free drink service on trains to hot chocolate on cold days, Auricle is testing how to turn data collection into a moment of two-way connection.

Curiko is a community platform connecting people with and without disabilities to shared experiences. Our goal is to create the conditions for convivial encounters between people whose bodies and brains work differently, where the focus is on shared passions, interests, and curiosities — rather than on one-way help, support, or care.

Like Bigby and Weisel, we’ve learned that convivial encounters are the product of …

Shared purpose, however fleeting (e.g roasting marshmallows, rolling a conversation dice, adding to a public sculpture, co-designing an idea)

Playfully flipping dominant norms — often by introducing different language, props, and scripts like offering a flight-like drink service on a bus.

Plenty of modelling — showing is so much more powerful than telling!

Opportunities to build confidence and capacity with difference — often through playing back stories and prompting reflection.

Removing barriers to authentic engagement — whether those are accessibility needs or paid staff who inadvertently stand in the way of their ‘clients’ participating in public space (e.g a paid worker preventing the adult with a disability they support from talking to strangers).

When we co-design spaces to facilitate convivial encounters, the offer is often well received. Because people (not all people — but a bigger swath that you might assume!) are wanting to be seen and heard. What we’ve found much harder is supporting social services to see strangers as a resource rather than a risk, and convincing funders that convivial encounters matter: that they are both a means to better outcomes, and a worthy end in and of themselves.

The tendency is to reduce encounters to activities and instrumentalize their value: to say activities only matter if they lead to long-term results like employment or reduced service usage. Activities are not the same as encounters. One can do an activity like life skills training, resume writing, fitness, or art without engaging or communicating with ‘the other.’ It depends where an activity unfolds, the roles people play, the objects or props on hand, and the script or frame.

Curating environments for convivial connections requires a good dose of intentionality, discernment of social norms, ingenuity to flip those norms on their head, and a willingness to redefine risk. Rather than see strangers as unsafe, we have to be willing to see strangers as a wonderful resource to cultivate. And rather than place so much expectation on structured activities to ‘deliver’ preset results, we have to recognize the value of fleeting encounters to shape our sense of self and community — and the ways in which repeated fleeting encounters build a convivial culture that can quell some of the discomfort, fear, and stigma that stands in the way of belonging. Indeed, a community comprised of convivial encounters is a far more inclusive and dynamic place. The phrase ‘culture eats strategy for breakfast’ aptly applies here. Culture eats programming for breakfast. As in, belonging and inclusion will come about because the dominant culture values people and relationships differently. Not because there is a social inclusion program.

Trouble is, most social service funding doesn’t operate at this cultural level. It operates at a programmatic level for a named group of ‘vulnerable’ people — adults with disabilities, people who are houseless, asylum seekers, etc. Funding for libraries and community centres can help, but tends to focus on physical infrastructure over the social infrastructure required to prompt convivial encounters and re-pattern normative social interactions.

As a new mom, it’s been delightful to gain a glimpse of what good social infrastructure can look like — facilitated play groups, story times, and music jamborees that bring parents and their little ones together. Because little ones do not know and deftly defy most social norms, they are incredibly effective at priming convivial encounters. The more my day is filled with pointing at big, furry dogs and laughing with the cashier at the grocery store, the more I wonder how we might we bring some of the curious and socially courageous spirit that babies draw out of us to other public spaces.

Beyond babies and dogs, how else might we prime convivial encounters? What might prompt you to squeal with delight, engage with a neighbour you do not know, or stop to talk to the person sleeping on a nearby sidewalk?

Check out this week’s prompts, and join us for an open practice call Thursday, May 29th from 2:30-3:30pm PST on this zoom link.

CONCEPT RECAP

What is an encounter?

Christine Bigby and Ilan Wiesel define encounters as “neither simply anonymous free mingling (usually seen as community presence) nor interaction based on established relationships (usually seen as community participation). They include fleeting or more sustained exchanges between neighbours, consumers, and shopkeepers, passengers and taxi drivers, strangers standing in a queue or sitting in a bar, beggars, and passers-by.”

“Fleeting encounters provide opportunities to be drawn out of “one’s secure routine to encounter the novel, the strange, the surprising” (Young, 1990, p. 239), or to “explore different sides of ourselves” (Fincher & Iveson, 2008, p.145). Beyond momentary pleasures, encounters are important to the way social differences are socially constructed and experienced. They are part of being included in a web of public respect and trust (Jacobs, 1962, p. 56), which may also expose one to different opinions and ways of life that contests ‘enclave consciousness.’”

What is the rub?

People who look and act differently to the norm are often missing from public spaces, or intentionally excluded — leaving many of us uncomfortable or fearful when we do encounter difference.

We tend to under-value encounters as a source of community belonging, and a staging ground for more sustained relationships across lines of difference.

Is there an alternative framework?

Bigby and Wiesel argue that the path to a truly inclusive culture runs through convivial encounters. In other words, convivial encounters beget more convivial encounters, which over time, shift our perceptions of others and reshape social norms. As they note, “Convivial encounters are marked by friendliness or hospitality, occurring when strangers engage in shared activity with a common purpose or intent, such as tending to a community garden or participating in community art group together.”

While we are often shielded from people who are quite different to us, when we do engage, it’s often through social services, volunteering programs, or other acts of charity. In these contexts, there is an inbuilt divide between the giver and receiver. In a convivial encounter, it’s two humans coming together, even if for just a brief moment, based on a shared desire, purpose, curiosity, or object of attention.

How can you apply this idea?

If you work within a social service context, you can reflect on the ways in which strangers (i.e people outside of the control of your service or program) are seen, and how encounters between community members across lines of difference are enabled or disabled. Where are the places and spaces where the people you support go? How many are segregated or managed spaces? What could it look like to create more opportunities for everyday convivial encounters to unfold?

Want to learn more?

Read Christine Bigby and Ilan Wiesel’s terrific article on convivial encounters

Take a look at guidelines for setting-up encounters between designers and people

Scan Erving Goffman’s 1972 book on Encounters