Happy summer, folks: This month’s practice calls are June 19 and July 3 from 230-330pm PST. On June 19th, we will reflect on the good life with Professor Eric Kim, Director of the Psychosocial Flourishing and Health Lab at UBC!

On one of my first dates ever, I proclaimed to the poor bloke in front of me that I didn’t believe in happiness.

Happiness, I argued, was a rather stifling aspiration more likely to lead to complacency than vision and grit — virtues, that for me, are at the heart of living well.

Unsurprisingly, my position has softened over the years. And yet, what I was grappling with as a haughty 17-year old (and continue to wrestle with as a chastened 40-year old) was a big idea: a good life isn’t simply a happy life. There’s so much more to the good life than a single emotion. Surely this is why legions of ancient and contemporary philosophers, theologians, and scientists have taken on the question: what makes a life worth living?

I studied social policy because I naively thought that was its purpose: to create the conditions for people to live well. And yet, wellbeing wasn’t an end outcome we talked much about, or used to stitch the silos together. Housing policy focused on availability and affordability. Employment policy focused on jobs and wages. Education policy focused on access, quality, and achievement. Disability policy focused on benefits and services. Workforce policy focused on training and credentials. The red thread between each of these issues wasn’t so much wellbeing as addressing market externalities and growing Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

GDP growth has been a central policy goal since the end of World War II, when it was adopted as a key indicator of a country’s progress. It’s a measure that calculates the total monetary value of all goods and services produced within a country over a year. And yet, as GDP has risen, population level wellbeing has not linearly followed suit. A hot-off-the-presses dataset tracking 200,000 people’s self-reported wellbeing across 22 countries found that GDP per capita was negatively correlated with meaning and purpose in life.

That mirrors what we’ve learned from a decade of ethnographic research alongside people living on the margins. What people who are materially deprived say matters most is purpose, connection, safety & control. Material resources — be it income, food, a roof over one’s head — can function as enablers AND barriers to purpose, connection, safety & control. Take a resource like supported housing with a blunt, one-size fits all policy prohibiting tenants from having guests stay over. While such policies have a time and place, they can also inhibit a sense of connection and control — the very things that turn a house into a home, and can propel people from surviving to flourishing.

In 2011, famed positive psychologist Martin Seligman published the book, Flourish, recounting his own shift in defining what matters.

“I used to think that the topic of positive psychology was happiness, that the gold standard for measuring happiness was life satisfaction, and that the goal of positive psychology was to increase life satisfaction. I now think that the topic of positive psychology is well-being, that the gold standard for measuring well-being is flourishing, and that the goal of positive psychology is to increase flourishing…

To flourish is to find fulfillment in our lives, accomplishing meaningful and worthwhile tasks, and connecting with others at a deeper level—in essence, living the ‘good life.’”

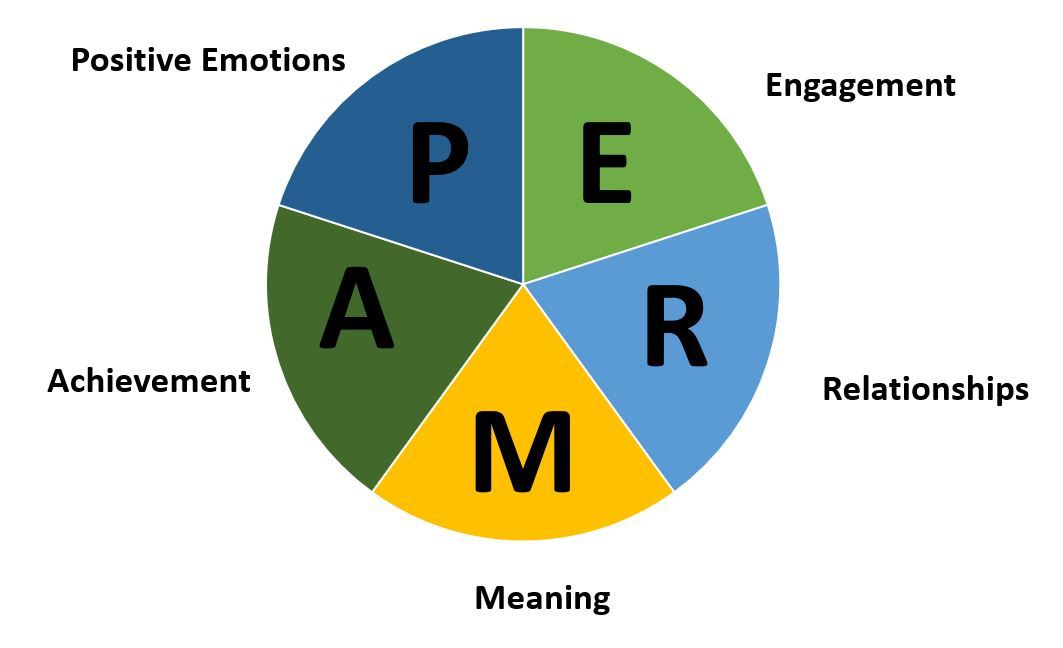

Seligman outlined five core elements of flourishing, using the acronym PERMA:

Positive emotions - feeling the good stuff: joy, gratitude, warmth, etc.

Engagement - being totally absorbed by what we’re doing; losing self-consciousness

Relationships - connecting to others

Meaning - feeling we matter; that there’s a point to it all

Accomplishment - a sense of competence & mastery

Seligman’s framework draws on the work of fellow psychologist Carol Ryff, who, in 1989, identified six pillars of wellbeing:

Self acceptance - having a positive attitude towards oneself, and integrating past experience, strengths and weaknesses into a healthy picture of self

Positive relations with others — being in fulfilling, trusting relationships with others

Autonomy - being able to make decisions that align with your values and desires

Environmental mastery - navigating the environments you are in

Purpose in life - having a sense of direction and feeling your life matters

Personal growth - continually learning and evolving as a person

Ryff and Seligman come to wellbeing from a psychological perspective, but are deeply influenced by the Ancient Greek Philosopher Aristotle and the concept of Eudaemonia — the idea that wellbeing isn’t a state, but an ongoing pursuit; one characterized by virtue over pleasure, and engagement over passivity. For Aristotle, Eudaemonia is the highest human good, not a means to some other end. In other words, wellbeing matters in and of itself, not only as a propellant of another outcome like employment or economic growth.

Contemporary Philosopher Martha Nussbaum recognizes that people’s ability to pursue wellbeing unfolds in a context. To live well, we need both capabilities and opportunities. In other words, we need to be able to do and be the things we choose and desire - that is the essence of freedom — and we need to have rights and resources to actualize what we value. Nussbaum names 10 core capabilities — ten beings and doings — that are essential components of wellbeing, each of which require resources & rights to enact. They include …

Life - being able to live a long and full life

Bodily health - being nourished, having shelter

Bodily integrity - having control over one’s body and the opportunity for sexual satisfaction

Senses, imagination, and thought - being able to learn, reason, create, collaborate, engage in ritual, seek meaning, etc.

Emotions - being able to love, grieve, be sad, have attachments to things outside of ourselves

Practical reason - being able to figure out what is good and what isn’t, and critically reflect

Affiliation - trusting others, feeling concern for others, being in relationship with others

Other species - being in harmony with and respect for other species & nature

Play - being able to laugh, have fun, relax, pursue interests

Control over our environment - being able to contribute and shape community, make political decisions, hold property, etc.

While all three frameworks highlight purpose & meaning, none of the frameworks explicitly name spirituality, awe, wonder, and perspective taking as key to finding purpose and making meaning. In part II of the ‘F is for Flourishing’ blog (the topic is soooo big it deserves a deeper dive!), I’ll explore what the latest research is revealing about the role of spirituality in flourishing, and why theorists like Carol Ryff now recognize it as a missing ingredient. At a moment when so much public discourse is reactive, and focused on safety and protectionism, how do we show that the growing paucity of meaning, purpose, and perspective is a root cause of loneliness, isolation, disconnection, and polarization? What does it look like to put meaning and purpose at the centre of our practice and policy?

Reflect on what flourishing looks like for you and your organization in this week’s prompts — and join us June 19th at 2:30pm PST for an open discussion on this zoom link.